Jon Henry

Jon Henry received the Film Photo Award in the Fall of 2019. Linda Moses catches up with Jon, taking a deep dive into his recent projects and meteoric rise.

Self-Portrait © Jon Henry

Linda Moses (LM): Could you talk a bit about your history with the medium of photography? Have you always been working with film?

Jon Henry (JH): Yeah, I started with digital, then I guess I started to transition towards film later on. I started switching it up as far as what the project said I was working on - what they commanded. Stranger Fruit, from the beginning I knew I had to shoot that large format, and prior to that I was using a lot of medium format for like portraits and stuff as piggy backs on other projects, so it was always a combination because a lot of the athlete work that I was doing, I was shooting digitally. So whatever I felt was right for the images for the set that’s what I used.

LM: That makes a lot of sense. When did you decide to start Stranger Fruit and how has the project evolved over the years?

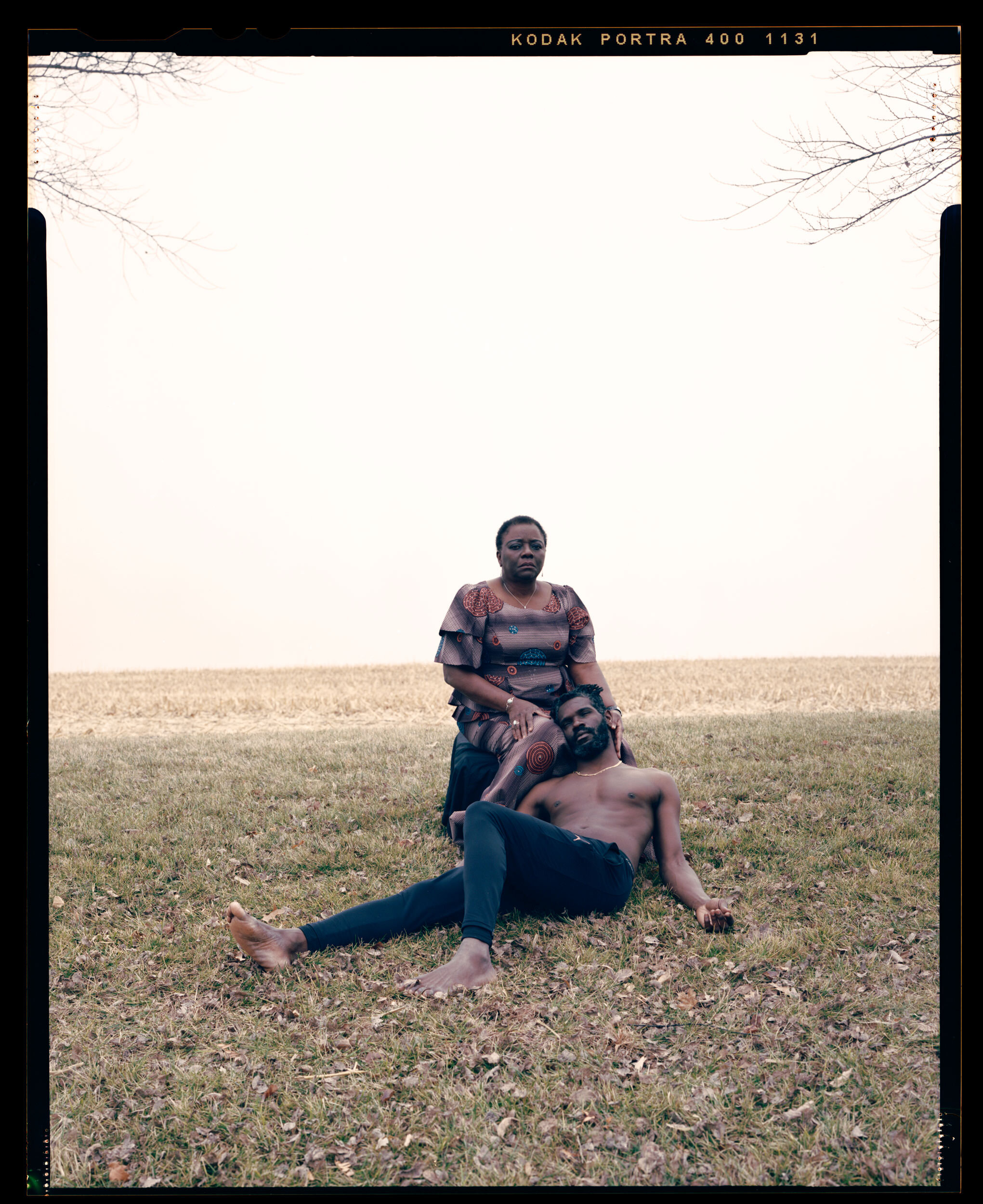

JH: So the project began in 2014. That was the first image that I made for it. But the concept really began in 2007 - so you know, it was a six-year period when I wanted to say something about it, but I just didn’t have the language to say what I wanted to say. So, I didn’t really know how to address it. Then, I went to school for a little bit, and the project began, and it was just a lot of research and studying the craft and living with the work for an extended period of time and then I was like, ok, this is how I wanna speak about this. And it basically all happened organically where I just started to work with the first full year of the project photographing friends and family, and then from there I was like this is something that I need to follow through with, something that I need to, really travel to see the whole scope of. And - yeah, from there I went state by state and area by area and just, you know, trying to get across the country as much as possible in all these different locations. So it started small and just grew from there.

LM: So you were starting with people close to you. Were you ever photographing yourself?

JH: No, the first family I photographed was a good friend of mine that I used to work with and same with the second and third one- a couple folks were family in that first year. One family reached out independently through Instagram but most of them were found through friends of friends in the various areas I was traveling to.

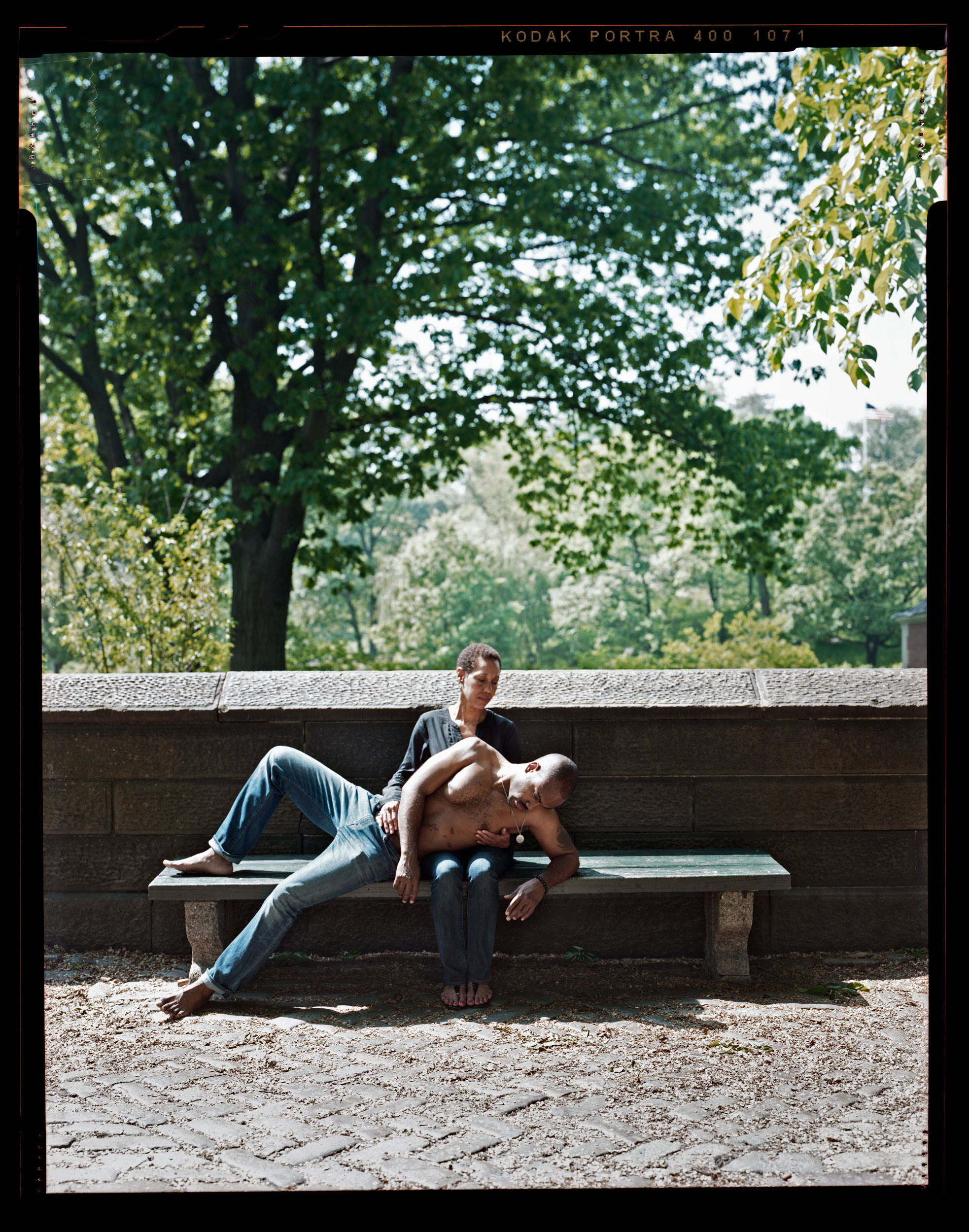

Untitled #10, Flushing, NY © Jon Henry

Untitled #61, Omaha, NE © Jon Henry

LM: I see. I’ve read that you worked as a sexton in Queens for a pretty long time. Could you discuss your experience doing that, and also how the time you spent with religious iconography influenced your decision to work with the pietà in this project?

JH: Yeah, so I worked in the church from Untitled #10, which was basically the first image of the project, for a pretty long time. I grew up in the church so I always used to hang around the church, so my first real studies of art were me just hanging out in the Met looking at paintings and looking at sculpture, spending pretty much all of my day there. So, because of that and because of studying the stained glass windows in the church, religious iconography was always pretty close to me and I always use that as a launching point for a lot of the projects that I work on. Not just this but the athletes work as well. Just always having that in the back of my head. Like I said, I was always around it and I knew the pietà very well - I knew that reference, I knew the piece, so it was pretty much an easy one-to-one when putting the project together. Like oh yeah this makes perfect sense, to just speak about the mother and son connection through art.

LM: And so, what exactly were you doing in the church? What was your day-to-day?

JH: I only worked on Sundays. I took care of the grounds, took care of the people because it’s the busiest day of the church, just make sure the place isn’t on fire, make sure everything is open, doors are open, heat is on, and everyone is safe. It’s a pretty big church, a historic church, over 300 years old. And we had three congregations: English, Spanish, and Chinese. So it’s a lot of people coming in and out.

LM: What specific paintings or pieces stuck with you throughout the making of Stranger Fruit?

JH: All the classical versions of the pietà from Michelangelo to Titian to Bouguereau, and there are many others, but they are just as important as the contemporary versions. Mainly Renée Cox and David Driscoll and even Andres Serrano. Knowing those images in the back of my head was enough to really put everything together for me.

Untitled #5, Parkchester, NY © Jon Henry

Untitled #7, Mt. Vernon, NY © Jon Henry

LM: One thing I really love about your images is that I feel you aren’t just responding to the pietà but you’re completely redefining it. Moving specifically into the ways you are constructing the portraits, I’m wondering what your considerations are when you get to a city and you’re working with a family. How do you pick a location within a city?

JH: It’s kind of hard to describe because it really is an inexact science. I’m looking for indicators - whether it be architecture or the makeup of the neighborhood that tells the story of the neighborhood or the city or the town. And that can vary from so many things - a street, an alley, a street corner, the way the buildings are made up, the architecture. It’s really bizarre trying to explain it. I’ll see something and I’ll say oh yeah, that makes sense to say that this is this location, but then that won’t work for another location. Also, tied into where the families are available. Because all the locations are where they live or where they work and sometimes we don’t really have a chance to choose - oh like let’s go here, or let’s drive 15 minutes away to shoot it here. Like no, we usually do it right where they live, like in the immediate area. So, it’s a bit of a process. Google maps helps with that a lot, so at least I can see before I get there. Because oftentimes I don’t have an assistant or a car so I can get around to be able to scout more efficiently.

LM: I’m drawn to the fact that you’re using color film and I wonder if you could talk a bit about why color, specifically? Have you always been using Kodak film?

JH: Color is pretty important to the work and to my work in general. When I was leaving school I must have gone through a year and a half of just shooting black and white and that was important to just focus on the content. But then I was like, color’s important to the way I see and what I want to convey. So yeah, it has to be color because it adds a lot more to the images and the locations and I think it would be a different project if it was black and white.

LM: I think it also makes these images quite dynamic and places them in the present moment. From what I’ve seen, the work seems collaborative, but I wonder if you consider the posing and staging collaborative? Do the families ever pose themselves?

JH: It does give the feel that it’s collaborative but it’s mostly -- like, they have the template, like I show them images before we meet, as far as like, this is what we’re doing, this is how we’re going to do it, this is what we’re going to do, but I pretty much stage everything as far as how the construction goes, how the compositions line up- you stand here you kneel here, this is where the body should flow, if there are other family members this is where you should stand. So, I’ll usually be the one dictating all of that to see what makes the most sense and visually how it works. Sometimes we have to change stuff up a little bit - make the composition work if the variations are off slightly. A lot of times I don’t know the scale of the mothers to sons; how big the sons are, and sometimes I don’t know how many children there are. Sometimes I’ll get there, and I’ll think it’s just one son and then it’s three sons, or it’s two sons and a daughter, or whatever it is. So then it’s like, ok what can we do to make this make sense visually in the limited time that we have.

Untitled #11, Buffalo, NY © Jon Henry

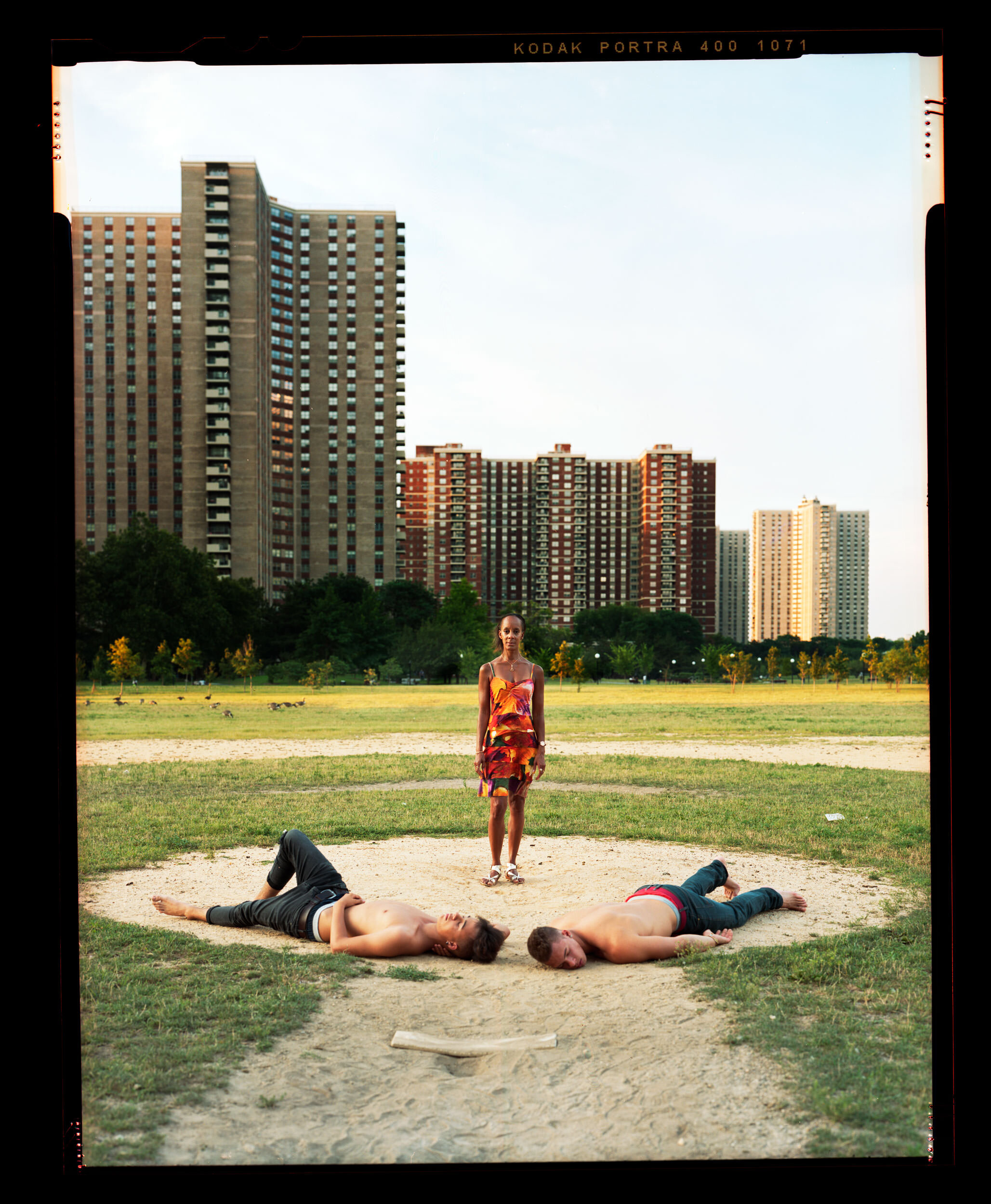

Untitled #1, Co-Op City, NY © Jon Henry

LM: Looking specifically at Untitled #11 Buffalo, NY and Untitled #1 Co-op City, NY, I’m interested in these because there is more than one son, and what happens visually when it seems like you can’t quite use the pietà. I guess I’m curious how you work with several people that you’re posing, and how did you decide the arrangement, particularly in Untitled #11, where one son is facing backwards and the other son is on the ground- both are looking away and the mother is looking into the camera, as with most of the images in this series.

JH: Yeah, it’s kind of random as far as how to pose them. Both of these images are family. Those are my nephews in #1. Because they are giants - they’re like 6’5” and 6’7” respectively, it’s crazy. So it was just like, how can I make this, lay the bodies out in a way that it still works even though she’s not holding them. And giving space and giving power to the mother. In #11, they are cousins. It’s kind of the same thing, again it’s two boys and I think two is harder than one or three because what does the second boy do? How do you make that new every time, how do you make it special without repeating the exact elements? So it just felt kind of natural to have him leaning away and have mom holding on to him while the other son is in that other pose that I repeated in #7. They are kind of repeating the same body position on opposite ends. It’s another inexact science, seeing what works.

Untitled #36, North Minneapolis, MN © Jon Henry

LM: I think what really strikes me about those images is the tension between motion and stillness which recalls life and death. Which is such an obviously prevalent theme here, because you are working with mothers who haven’t lost their sons yet speaking to the real fear and grief that is present. You said that in these images you are working with family, but when you aren’t working with family members, what is it like meeting people for the first time and working with them, engaging in what I imagine is quite a difficult and intimate gesture?

JH: Yeah, it can be difficult. A lot of times we keep it pretty light on set so that everyone is loose and comfortable. I’m working on their time frame, so I don’t have a ton of time to make the images. Sometimes we literally only have twenty minutes, sometimes we have an hour. They already know what the expectations are and then it’s just a matter of getting the camera set up and built, and then getting them into frame, maybe do a test run so they can feel how it is. Especially if the weather is a little colder, and then I’ll have the son take off his shirt and go barefoot. Also thinking of the mom, if she is resting on her knees, making sure that she’s not in pain or in that position for too long of a period. Even though it’s large format, the images happen kind of quickly, which is a little crazy. Somehow, it all comes together and we’re able to make it happen.

LM: The idea of slowness in relation to the work, and time in general, is something I keep thinking about. Because even though maybe the picture-making process itself is not that long, it seems like there is a lot of time that goes into the before and the after and the time that you’re spending making sure that it feels like a caring act. In relation to so many quick images in the media, I wonder how working with film and especially large format makes you think about the function of time in relation to the project?

JH: One of the beauties of the project is the stillness that the images have, even though they are in such familial (familiar?) locations, whether the background is quiet or busy, it’s sort of hard to describe. All these things are going on at once, but here’s this slice of time and this parallel universe where these families have to consider this on a daily basis. But then here we are just reflecting on the fact that this could be happening to any one of these families at this exact moment. So, I don’t know, it’s definitely layered and complex and heavy to think about. Even just making the work.

Untitled #57, Houston, TX © Jon Henry

LM: There seems to be a lot of trust involved between you and these mothers and their sons.

JH: Definitely. And you know, I would say all the credit in the project goes to the mothers, just for being open to being this vulnerable. Because there are so many families who can’t do it. Who I’ve reached out to and who support and love the project but don’t feel that they can put themselves in that position or don’t want their sons to be in that position. And I completely understand- for some, it hits too close to home, but yeah, like I said the credit goes to all the families in the project from so many different backgrounds and circumstances who are able to be a part of this.

LM: I really like the way that you decided to photograph mothers isolated as well, and have them respond in text to your pictures. I wonder if you could speak a bit about when text entered the work, and also if the text that is a response to your work then inspires new images that you want to make?

JH: Yeah, the text is kind of isolated to the project, as the questions really revolve around what their expectations were coming into it, how they approach the subject with their sons if they do yet, and have them describe the action of holding their son in the image, because I send the survey when I send the final image. So, then they see the final image, which will be a week or two weeks after we’ve made the photo and then they can see it as a one-to-one. So then it all comes back to them, what that felt like in that position in that time. So, I’ve asked them to speak about that once everything is set. And the images, the survey of the questions, and the text from the moms came from one of the first families I photographed in the first year, 2015. Nefertiti - she reposted the image on Facebook and wrote this amazing poem to go along with it. I was just like, that’s perfect. Because I was looking for what the third part of the project was. And I really wasn’t sure what it was, because I had the image of the mother-son, I had the images of mothers by themselves, but still, it felt like something was missing and I really didn’t know what it was. So having the text from the moms really solidifies everything. That this is something very real and this is why it’s so important. The images and the statement are my words, but having the words from the mothers in the project really took it to another level.

Untitled #51, New-Orleans, LA © Jon Henry

Untitled #53, North Little Rock, AR © Jon Henry

Untitled #54, North Little Rock, AR © Jon Henry

LM: Yeah, definitely. In thinking about the pictures of isolated mothers, I wonder how the staging differs for those pictures? I notice that many of these pictures are taken indoors; what is the difference for you working within someone’s home versus the considerations that come up when working outdoors?

JH: Well, I guess the issue is that the second image, the mother in isolation, is always the harder one to make. Typically because when I’m thinking of scouting everything, I’m thinking about the mother-son image first, because that is the most important one. And then, it gets based on how much time we have, if there is a place we can scout real quick. Usually, the mother solo images are shot right next to or right around the corner or in the same exact area from the first image. So, sometimes it doesn’t work because sometimes I make a lot of mistakes making those images. I don’t always want to shoot those indoors because it’s like, how do you make that new every single time, how do you make that compelling every time you go out there. Sometimes they come out, sometimes they’re not as interesting. But then you have some images that come out and it’s like, oh yeah, this is an interior this is perfect. Like Untitled #36 in Minnesota. It’s like, this front area of the home, and it’s just like, the repeating yellow, the little sculpture looking one way and her looking out the window and the chess board- it all comes together and is perfect. So, sometimes it really comes together and sometimes not so much. Those images are always the harder ones to make and I usually don’t have as much time to make them.

LM: Did you always want to pose the mothers looking away or did you have iterations where they looked at the camera?

JH: I always wanted them looking away, because I wanted it to be a balance off of the first image, the mother-son image where all except for one image are looking directly into camera. So, for these images I didn’t need that anymore, I didn’t want them to look into camera, I wanted them to look away and I wanted the viewer to put themself in the mother’s shoes. Say like this is what’s going on in the scene. [To see] how the viewer reacts, how they respond.

LM: To return for a moment back to the pietà images, I am curious about how you think of your own presence in these images. I’m speaking to the fact that the mothers are often looking directly at the camera and thus at you and the viewer. How do you think about yourself in relation to presence in the image?

JH: I don’t know, I mean I’m just thinking of creating the work and I’m just looking at everything in the image to make everything, trying to make everything as perfect as possible. Not really perfect, but just make sure everything is aligned in how I would want it to be represented. So, I’m rarely thinking of myself, I’m thinking of their comfort, how the bodies look, how everything is organized, hand placement, everything like that. That’s what I’m thinking of the most.

Untitled #3, Harlem, NY © Jon Henry

LM: Untitled #3 Harlem is one of the few images in which the mother is looking down, returning back to the classic pietà. I wonder what that shift means symbolically to you, or how you think about it?

JH: That was one of the early images, the second family that I photographed for the project. Visually, this was the one that made the most sense and came out the best, but then afterwards, working with a couple families after that, the mother looking into the camera was really important and I wanted to drive that home. So, this ends up being the only image where the mother isn’t looking into the camera. And that’s fine - it’s good that the project has that… is open enough where things like this can exist. Just like in Untitled #11, he’s the only one who has shoes on, and everyone else is barefoot. So, some say its concessions are made...

LM: Yeah, I don’t think those shifts take away anything, and instead add another dimension to the work. Thinking about the moment that we are in currently, and how tumultuous of a year, few years that it’s been, what has it felt like to travel the country and make this work amidst continuing police violence and also during a pandemic? How has that shifted your thinking or created obstacles in making the work?

JH: Well, it’s been difficult because we couldn’t travel for a couple of months. Thankfully I was able to get out in January to photograph a number of families in New Orleans, Little Rock, and Houston. I photographed four families in a three-day span at the beginning of this year, and that was huge. That was the first big thing after the film had come in through the award. I was pushing to get on the road as soon as possible, not knowing what was going to happen for the rest of the year but just knowing that I needed to make these images. Thank goodness I was able to get on the road because the next family I was supposed to photograph was in April and everything, of course, had been shut down by then. I just came back from St. Louis a few weeks ago where I photographed two families. I’m still trying to wrap up the project and get to Utah, Nebraska, but yeah we just have to wait it out. Like I said I was supposed to be there, about to buy tickets to go there in April but that’s when everything was shutting down. I’ve just been sitting and waiting because I couldn’t do anything - couldn’t travel, couldn’t make images, waiting it all out.

Obviously with everything that’s been going on, the work has just exploded again. Which is both good and bad. Because it’s being seen by a much wider audience, but again at what cost? More lives have to be lost for people to realize we’ve been talking about this for years? So, it’s stressful.

LM: Having gotten the grant and being able to work with so much film, how has that shifted your process? Do you find yourself taking more photos in a given situation?

JH: I keep it pretty consistent. I don’t shoot more, I just shoot exactly what we need, which is typically 2-5 photos per family. So, usually it’s around three, depending on how much time we have. If we just do the mother-son set then it’ll be two sheets, maybe three sheets, and then that’s it. So I don’t like to overshoot, because then it overcomplicates things. And then also I don’t feel like I need to shoot eight photos to get the one or two that I want. If we set everything up, do it in two shots, I know one of those two shots is gonna be it, and then we go on from there. So it ties in with the time. Sometimes you just don’t have the time to make 8 images or 5 or 6 images; plus, I don’t want to then have to scan all of that stuff and sit in front of the computer editing all that stuff. I just want to, you know, just focus on the one or two images and just work on those. However it falls, that’s what we do.

LM: Yeah, that makes sense. I’m curious about some of your newer images. Are you still working on them?

JH: I haven’t finished the St. Louis images because I just got back. One of the Little Rock images is on the website - Untitled #55. I don’t think I have the other ones up there yet but they’re floating around on Instagram.

Untitled #48, Inglewood, CA © Jon Henry

Untitled #56, Houston, TX © Jon Henry

LM: Could you talk a bit about Untitled #48, and how you conceptualized this image?

JH: I photographed in Minneapolis at the beginning of the year, photographing because I wanted to have black bodies in the snow. I was trying to also use that logo for several reasons. One, it’s a circle and acts as a halo. But then, the bullseye, and just the word itself: Target. It had all these layers to it. I wasn’t able to use it out in Minneapolis because we just weren’t near the location and it would have been a thing where we would have had to drive 15 or 20 minutes to try to make the image and it just didn’t really work. But when we were out in California, it was like, this is the time because this family had driven a pretty long way to meet me. So, I said, ok, we’ll make it here and figure it all out. It was crazy - I hadn’t even posted this image until this year because I had taken it pretty much almost a year to the day when everything was exploding after George Floyd. I posted this and that’s how the project exploded again. But yeah, again just thinking about the symbol and what that means. How these men, women, and children are targets. But also, this reverence of the halo. Having the dual meaning was really important and was something I thought about for a long time before making the image.

LM: I’m also noticing the way that light itself plays a role in so many of these images. It reminds me of the relationship to religious iconography and the idea of the spotlight; how that ties into notions of slowness and contemplation. This work is both urgent and slow, in a way - because it involves grief and pain but is also a very urgent call to action. So, I really admire that a lot, and can’t emphasize enough that these are really powerful images and thoughts

JH: Many thanks.

LM: What are your next plans for the project? Are you planning to continue, or are you wrapping things up and thinking about book form now?

JH: I’m trying to wrap it up - literally just before we started the talk I was following up with two families in Utah because I’m really trying to get out there and get to Nebraska, hopefully as soon as possible. I do want to make those last couple of images and then start focusing on the book and working on that. Because yeah, it’s been six years going on seven now, and the project has said what it’s needed to say and I’d like to wrap it up because there are other things I want to photograph and other things I want to tackle visually. We’ll get there.

Untitled #58, St. Louis, MO © Jon Henry

Untitled #60, St. Charles, MO © Jon Henry

LM: Well that’s exciting! I look forward to the book, for sure. I’ve been seeing some images of public installations; how does it feel to see this work around New York City?

JH: Yeah it’s pretty surreal. It’s definitely a great feeling, I’ve always been interested in public installations from the time I saw Felix Gonzales-Torres’s piece of the unmade bed - so I’ve always been interested in that. It’s just another way for people to engage with the images; thinking of the audience, I don’t want the images to just live in the galleries because only few people can go to the galleries or museums. I’d obviously love for the public to engage with it.

LM: Yeah, the work needs to be seen in as many ways as possible.

JH: I’m always interested in showing the work in smaller spaces, more community spaces, and also publicly. See how that changes, how it affects people.

LM: For sure. I’m really drawn to the way these pictures hold so many different emotions; from grief to power, fear, and love. As you’ve already said, it’s an emotional process. What does working with these families and making the photos teach you?

JH: The importance of the story, of what it is that we’re addressing. Just, how important it is to these families and how it really does affect this community across the country. You really can see that through the texts, especially. Because the text is not the same answers being said by different people - it’s really a range of emotions; how people say how they have this love for their son, love for their family but also this fear that something could happen to them. No matter what age they are, and it’s just really beautiful to see. Like I said, I give the parents, the mothers, so much credit for being a part of it. Just seeing that is really impactful.

LM: And I’m sure you’re creating lasting connections with these families.

JH: Definitely.

Untitled #62, Omaha, NE © Jon Henry

LM: What’s been inspiring you lately? Art-wise, music-wise, anything you’d like to share.

JH: I’ve been listening to a bunch of different music – I’ve been taking in a lot of art from a lot of different places. Looking at a lot of young im age-makers, especially young African American image makers, because a lot of folks are really on the rise right now. So that’s been really cool and really great to see. People getting their shine as opposed to like five years ago when we probably wouldn’t have heard the names of Tyler Mitchell and others. It’s been nice to see all these folks that I’m following and the covers that they’re shooting, the projects they’re working on, and them getting the shine as well. So that’s been really good. And seeing them work definitely inspires and makes me want to work even harder, so that’s always cool.

LM: It’s so cool how art inspires art. I love seeing all the work being made right now - it’s incredible and so inspiring. I’m so excited for you and this work! It’s a crazy time, and I hope you take care and continue to find rest. Thanks so much for meeting with me, Jon.