Natasha Lehner

Photographer Natasha Lehner won the Film Photo Award in 2023. Jack Fox catches up with Natasha on her work.

© Natasha Lehner

Jack Fox: What initially drew you to photography and what keeps you working within this medium? Why film?

Natasha Lehner: Photography has always been a part of my life. My dad is a photographer and growing up, he always had (and I now have) many of the cameras that he had when I was young and growing up and watching him photograph. Because of that, film was always a part of my life when I was first learning to photograph. All we had was black and white film because that's what my dad used. And so it was never really a creative or aesthetic decision that I was going to be photographing in film. It's just what was around. There was a drawer that I would open and magically there was always film inside of it. So I never questioned it. And that followed me, I remember being five or seven and getting my first camera at the antique store with my dad. But it wasn't until college that I really decided that this was something I would want to commit myself to. And that was endlessly generative for me. I had dabbled in digital, but I never felt that same kind of spark as I did with film. I think I’ve really narrowed it down to the tactile elements. I like being able to follow the physical form from inserting the film to holding the final print and having control over the entire process is something that is very exciting to me.

JF: Was your dad a hobbyist or was he a professional?

NL: Well, he's a really big part of the larger story that takes place in the project that I was working on with the Film Photo Award. And so he would call himself an amateurist. I would not. He consistently in his life went out of his way to pursue photography in ways large and small. He's an English professor and he found ways to work in the darkroom even when it wasn't his profession. So he would do trades where he was the one basically being the lab tech and in exchange, he would get to use the darkroom after hours. Then at a certain point, he built his own darkroom set up in the basement. So it's something that consumed a lot of his time. He's amassed quite an archive, which I have now kind of inherited and have worked through. So I've seen a lot of the world as he's seen it. And I wouldn't say there's anything amateur about it. But he would probably say otherwise. I'm just very adamant that that's not the case.

JF: Do you see any parallels or similarities in both of your photographic eyes?

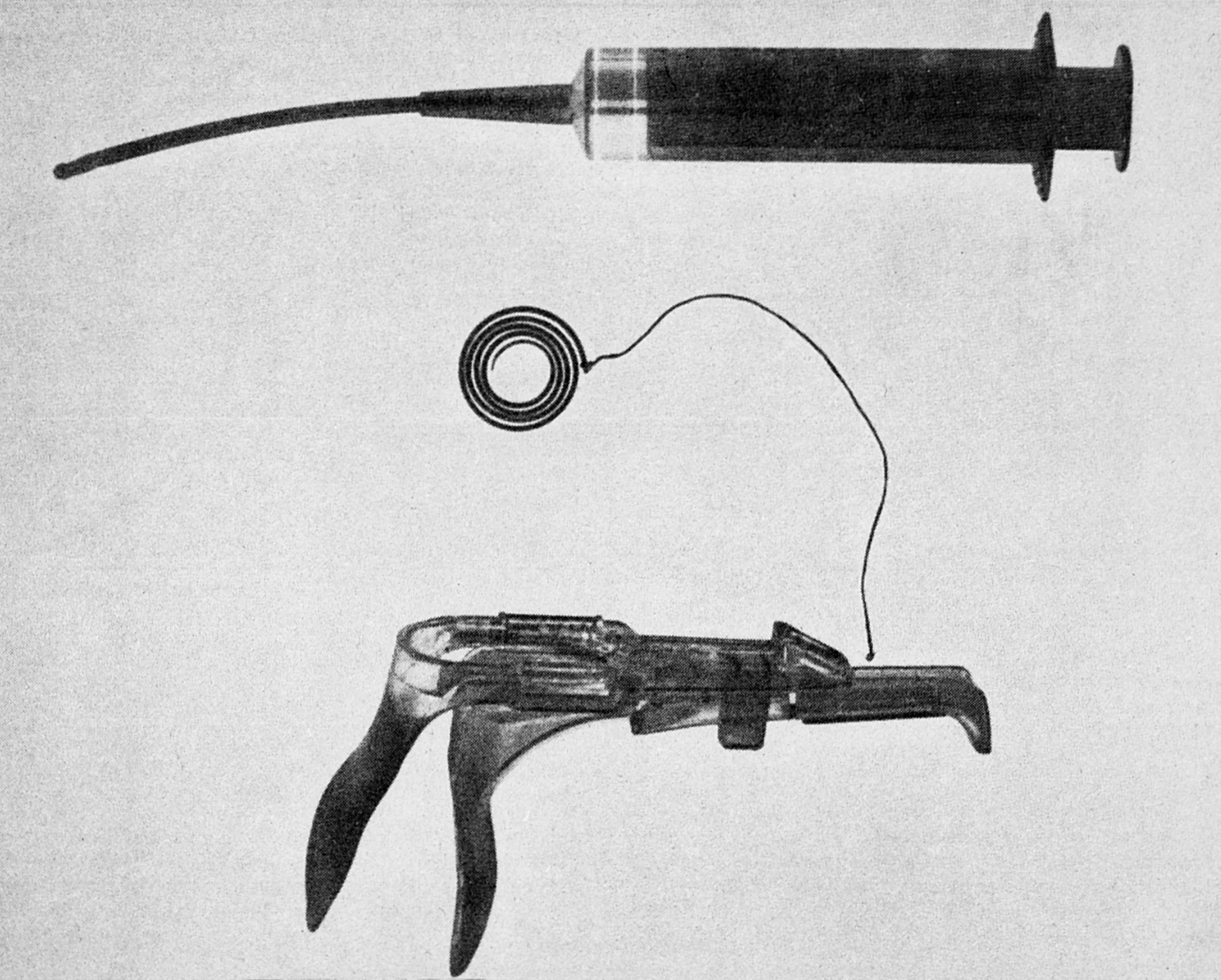

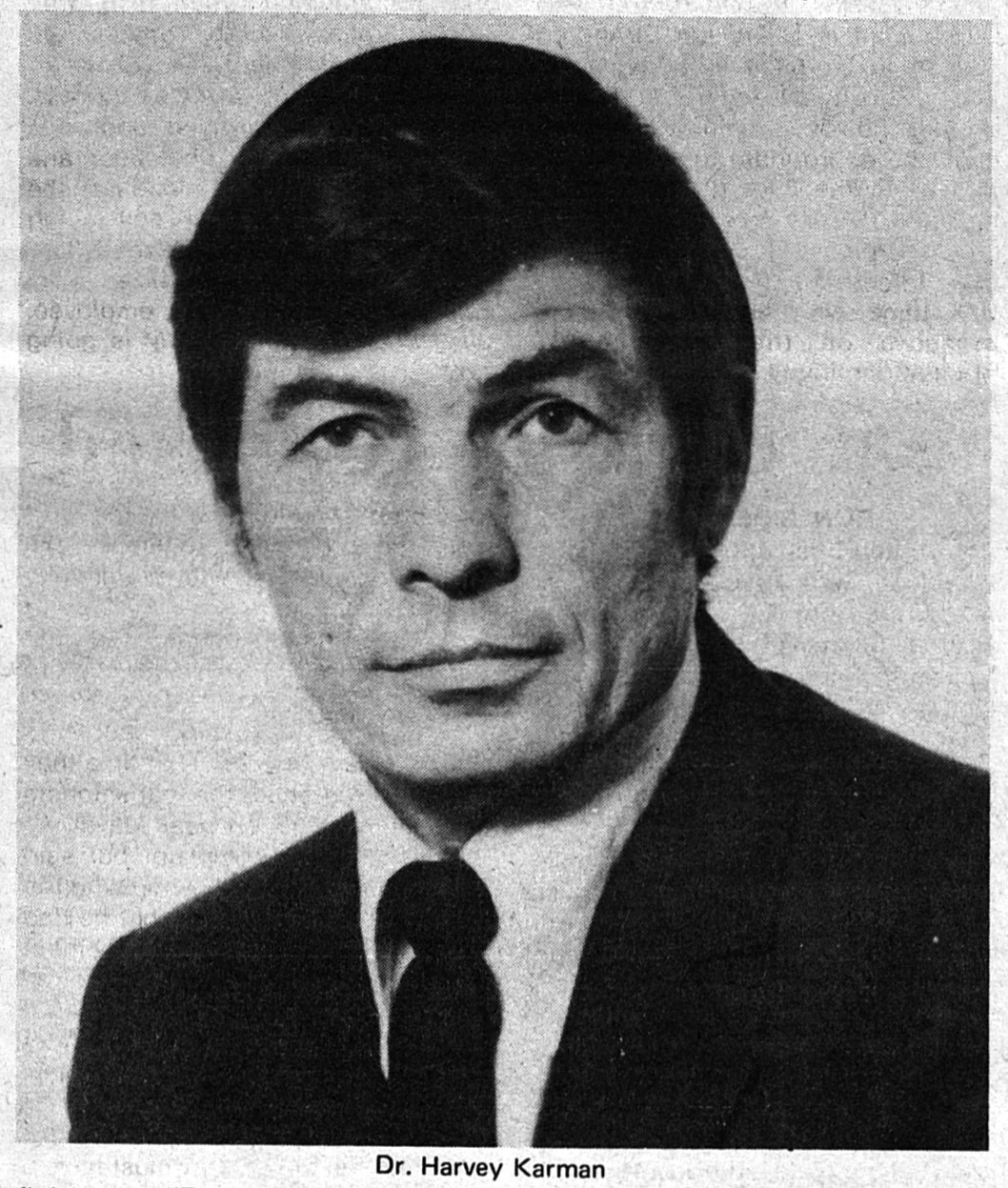

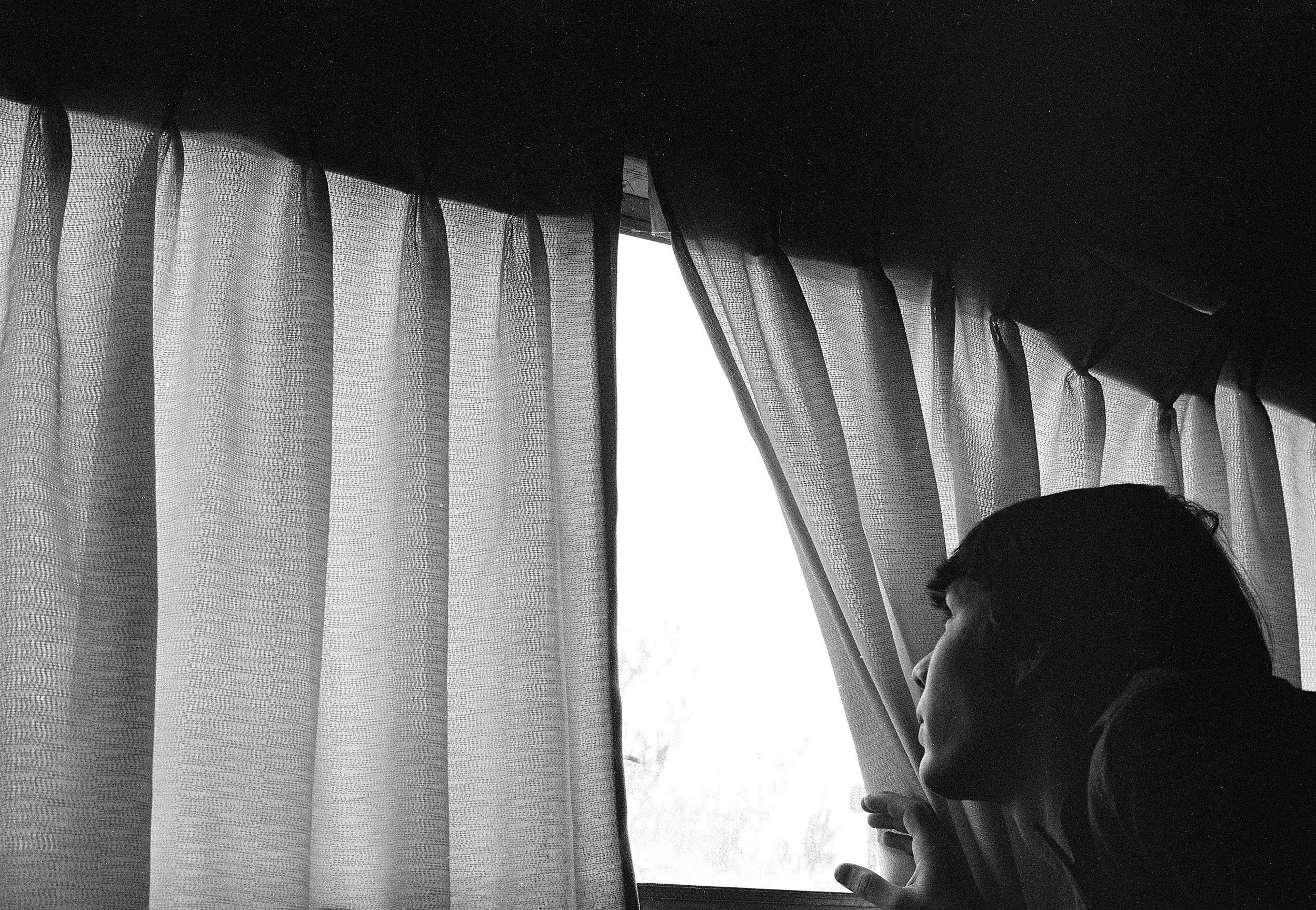

NL: Hugely. That became a central part of the impetus for my graduate thesis project and the proposal that I gave to Film Photo Award, which was my thesis project called More of Everything, which is a project about my recently discovered biological grandfather, who was an abortionist in the 1950s and 60s, and also at the forefront of the emerging fertility movement at the time. My dad discovered his parentage through genealogical testing and in addition to discovering this man, Harvey Karman, to be my biological grandfather, we also discovered at least 15 biological half-siblings of my father's and this kind of incredible web of family that formed. So I was really fascinated in figuring out more about my biological grandfather. He was a complicated figure. He was very present in the media at the time. This is all before abortion was legalized. He wasn't a licensed medical professional. though he operated an underground clinic. I was fascinated by his media presence. And it wasn't until I went to LA for the first time and I met this incredible family of relatives that I discovered my biological grandfather's personal archive for the first time. Unbeknownst to me, he was a photographer and a writer in his own right as well. I uncovered images, poems, screenplays, and essays that had been in boxes in my Uncle Steve's house. I spent the better part of a year digitizing a lot of this archive and in doing so found so many similarities in how Harvey photographs and how my dad photographs and how I photograph and how we write. And it felt very much like an inherited trait and prompted a lot of questions about nature versus nurture. This is something that was kind of innately within all of us, especially because we didn't know Harvey until after he had passed. So it became kind of a generational story in many ways too.

JF: And to be clear, he wasn't in your father's life or your life because he was a sperm donor?

NL: So the backstory is that my grandfather that I knew growing up called my dad about 15 years ago when he was about to go into open heart surgery and confided in him that he wasn't actually his biological father and that in the 1950s they had secretly resorted to using a sperm donor, It was just very, very secretive at the time. My grandma and grandpa decided to keep it to themselves and raise this child as though it was completely their own. He has brothers that were also told this information, but they just thought, as far as we're concerned, you're our father and that's all that matters. But my dad reacted quite differently and quite strongly and was curious to find whoever this biological father might be. It ended up being a very long journey because this was pre-23andMe, pre-ancestry.com. So this was very much on the ground research and figuring out as much of this information as he could. For no fault of his own, 10 years ago, he found the wrong guy. And then, it wasn't until about four years ago that my sister gifted my dad 23andMe for Christmas, and he took this test. If you see a photo of Harvey next to my dad, you don't need a DNA test to know that they're related. The first time I saw a photo of Harvey it shook through me. I couldn't believe the resemblance. And everything down to the hands, everything looked so familiar to me. I was very fascinated. My dad will often say that the story ended for him when he discovered Harvey, but that's really where it started for me. I was fascinated with figuring out more about who this person is, what his life was like. Trying to get as many firsthand accounts as possible, from people that interacted with him, whether it be family members, colleagues, people in the movement that knew of him more socially. So it's been a long, ongoing process.

JF: Would you say that your dad was able to find closure through this confirmation that Harvey was his father?

NL: I think in some ways, yes. I mean, certainly I can't speak for him, but I think my dad would maybe agree that the more information we had about Harvey, the less we felt we knew him. I was doing pretty extensive research, going through a lot of online databases, newspaper archives. trying to source as much information as I could about this person. With every finding, I just felt more and more confused. My dad was a huge collaborator of mine throughout this entire process. So any writing that I had done as part of this project, he was my first editor. Any photograph that I had taken, he was either part of the making of the photograph or part of the editing of the photograph after that. He saw every edit of the project. And he wrote a beautiful introduction to the project as well, where he explains more of his experience. I think that there are certain parts of Harvey where he can find himself. The title of the project, More of Everything, comes from one of the many poems that Harvey had written. He used that one phrase, 'more of everything,' a few different times in different poems that appear throughout the book that I subsequently made. So, more of everything felt like a perfect descriptor for this person because he was this kind of larger than life figure. I felt like I could never get to the bottom of who this person was. This very elusive figure in my mind. So I think he is someone that poses more questions than answers. And at this point, we just generate whatever meaning that we can, regardless of how based it is in fact or not.

JF: Since you're weaving three generations of photographs in this body of work, the pictures range widely from photography, self-portraiture, archival discoveries, and of course writing and poetry. And the images in it range from very clean images to images filled with detritus, scarring and printing marks. I'm curious why this mode of working made the most sense to you and why that freedom was important to you in making this work?

NL: Yeah, I was working with so many different materials, as you mentioned. Archive is really what I was leading with, though, in terms of structuring the larger project. I felt that while I was using such a vast array of materials, whether it be media archive, personal archive, images I was making in response to this printed material, historical context through writing. The material varied greatly, but what I could make consistent was its physical presentation. I came up with an outline for the work, how it was going to be physically displayed, that would differentiate the materials. Maybe it only made sense to me, but it was very much a mode of organizing so that I could easily distinguish one form of media from the other. I would say what built that consistency was this tactile component that has really been what's drawn me to photography all along. I really want to bring photographs into physical form and see them on a wall or in a book or scraps laying all around. I want the evidence of life. And so that became my through line for the project. Where I could find one. I mean, at a certain point, I was completely overwhelmed with all of this—indeed, an incredible mass of information that I had accumulated. And I was really struggling to find my voice amidst all of this material and what my kind of creative infusion would be into this very documentary project that I was working on. Proof of life really became my signature— or how I felt I was inserting myself into the project by really controlling.

JF: How do you approach the sequencing and design, and how do you make sense of it all in a book form? What is your approach to sequencing and design work generally?

NL: I have a background in both graphic design and photography. My undergraduate experience was technically design communications with a photography emphasis. So the two are very much intertwined in my life and in my practice. The second I start photographing, I'm immediately trying to figure out what kind of end product this might look like. Iterating book form is a central part of that creative process. I'm building an edit and then in real time, I'm printing it out and making some sort of primitive or elaborate book dummy. That, again, lends this very tactile component. I like to be able to stitch things together and figure out how everything's going to fold into itself. It was all being filtered through InDesign in real time. I also had a very elaborate filing system digitally to try and make sense of everything for myself. I think one thing that specifically the Film Photo Award allowed me was freedom to explore every potential option for executing this project, as I could see 50 different avenues that I could take this project down. I really needed to move through all 50 before I landed on my final product or a version of the final product. The final product is greatly withheld in a lot of ways. I think as I struggled through the project, I assumed that I had to come to some sort of conclusion or I had to give viewers a definitive answer as to what they should think about this person, what kind of facts I was going to divulge about this person and their life. How that informed my father and myself. I quickly realized that, actually, what's more interesting is to invite viewers into the questioning and to allow them to discover this person in real time for themselves. So the act of withholding became really crucial in the edit because I wanted to slowly reveal who this person was and present different versions of this person and allow the viewer to experience the same confusion and questioning that I experienced. There were a lot of definitive answers I could have given to this body of work, but I think that would have diluted the power of the messaging to begin with. In the case of my father too, I didn't ever want to be in a position of speaking for him. This was also a way to allow for all of us to move through this emotional experience together.

The physical book and all the ephemera that I designed around my thesis exhibition was presented in the form of medical documents. The physical book is a perfect bound manila folder, basically. And I'm interleaving medical supply papers through various pages. I'm printing on Xerox paper because I wanted to give this kind of tactile effect that was very different from the perfectly printed and polished works that were on the wall. I wanted something that could intimately fit in your hand so it felt like an experience that you could move through independently. I didn't want to provide any written context. I wanted people to be able to look through the images, look through the archive, and piece together this narrative. Then at the end, I have my essay, my father's essay, and then plates that give credit, titling and dating to all the material. So people could kind of go back and forth. Then when they have further context, have this kind of revelation as to who made what, when. The reality is it's material of over 70 years or more in the making. My thesis exhibition was 85 works on paper, and the book was about 150 pages. So it's a pretty overwhelming story to walk into, but this is my attempt to make it as concise and honed in as possible.

JF: I think it needs to be overwhelming. Making all of these discoveries must have been overwhelming for you and your father. That's how the work should feel in response.

NL: I mean, even going back to the title, More of Everything, it's just overwhelming and everything kind of goes off to infinity.

JF: Do you see this project as finished or will it ever be finished given the vast majority of material? What life do you want it to have?

NL: Yeah, it's a project that I think I'll carry with me throughout my life. I don't think there's any point of closure. It's always a question that I have in the back of my mind, but it's something that ebbs and flows. After I finished my thesis project, I was a little bit exhausted from the project, but what I've realized is that I used a lot of the structuring that I built as part of that project and carried that into newer projects. It gave me a real clear structure as to how to execute something. A mode of working that I felt really drawn to and a mode of questioning. Those are things that I carry in my day-to-day life and are brought into every project that has been envisioned since that one. I do hope that it has some form of half-life. I do want for this to be a living, breathing archive that people can go to and see and experience for themselves, but also I think I just need to live with the work more. Maybe at some point the world will tell me when it needs to go out and live its own life. But for now, it's something that I hold close.

JF: What are you currently working on?

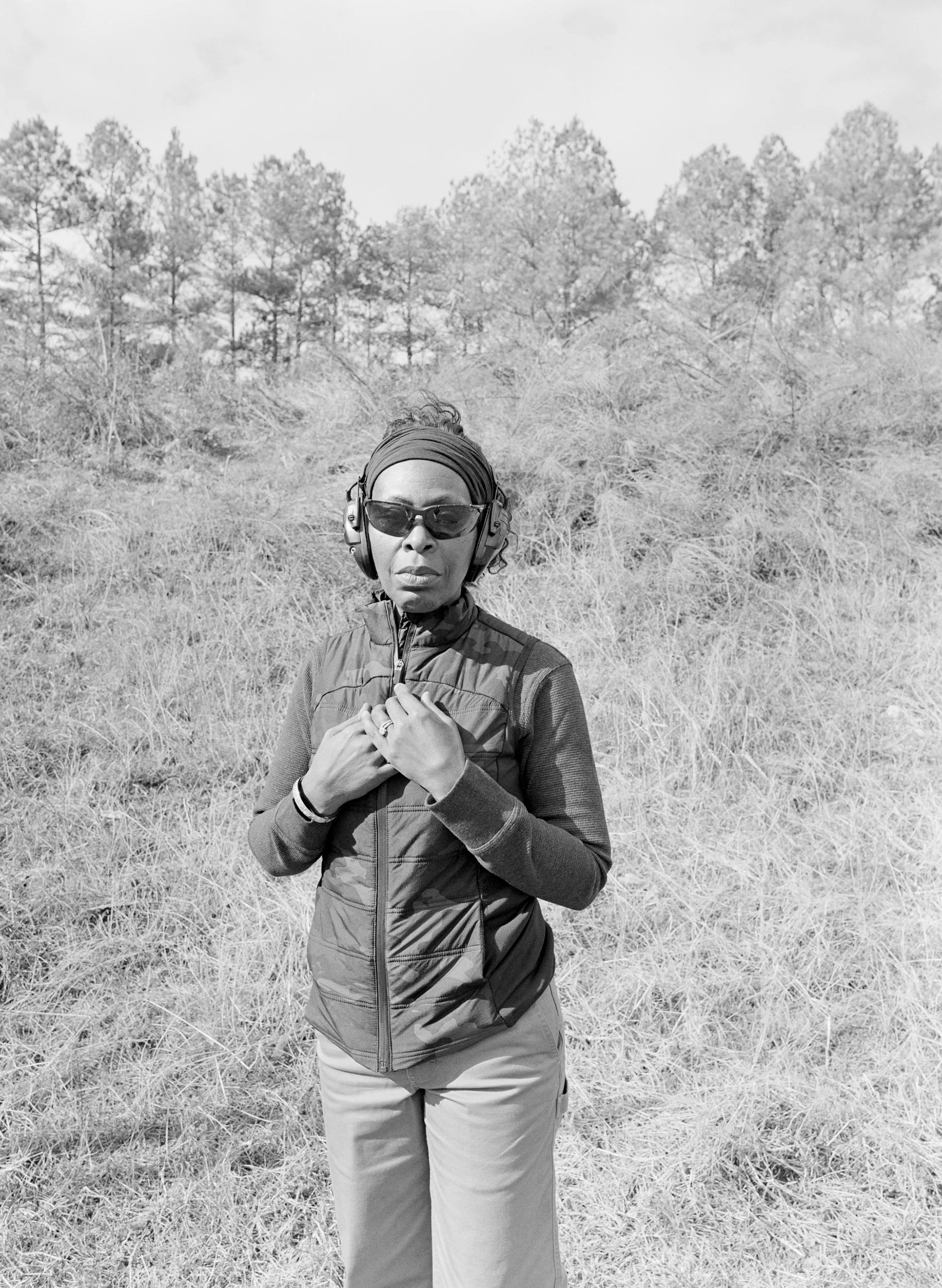

NL: I have a few different projects. One that's been all-consuming recently is called Iron Sights, and it's about the parallel histories of photography and weaponry. Which is something that's always been on my mind, too, because in addition to having always been a photographer, I was always a marksman of sorts. My dad is an Army guy. And when I was young, he taught me how to shoot and we would go to the range together. It was partially just— really precious bonding time with him, but also partially something I really enjoyed doing. I always saw these similarities between photography and weaponry and certainly within the terminology of the two. It's a project that's much more rooted in photo history. As part of the project, I've been working with a few women's gun clubs in the area. One in particular, the Women of Steel Gun Club, I've been very involved in. I'm now a range safety officer and I go to a monthly gun club. I also go to the 2-Gun Rimfire competitions. And I've just really found a hunger for that community. They've been so welcoming in letting me photograph and move through this line of questioning, which has been great. Another photo project I've been working on here is called Blendline and it's about dirt track speedways in North Carolina. So I'll find a speedway and I'll get a pit pass and I'm photographing a lot of the inner workings in the pit of these speedways. I have a real fascination with these female race drivers. It's a huge endeavor to get these cars ready for a race. And it's really generational. People bring their families. A lot of the women I meet have learned from their fathers and their grandfathers and their brothers are there helping them. I'm very fascinated by that world. So that's been a very fun project, too, that has brought me into new parts of the world.

JF: Amazing.