Shawn Bush

Photographer Shawn Bush won the Film Photo Award in 2023. Jack Fox catches up with Shawn on his work.

© Shawn Bush

Jack Fox: What initially drew you to photography and what keeps you working within this medium and why film?

SB: I started photography through video. I grew up skateboarding, so it's kind of natural. Video is essentially the currency of skateboarding. At a certain point, I got tired of following people around to record the desired trick landing. Around that time, I was taking a black and white photo class and began to become more interested in photography - stopping motion, elongating motion, lighting, all that kind of stuff. I transitioned away from 35mm and began shooting with a medium format camera, color slide film and two or three external flashes, which was the normal skateboard setup for the era.

Around that time, I was given an enlarger and made an extremely unsafe and small darkroom in my parents’ basement bathroom. I started with a love for film and the amount of thought it took to light, expose and create a defined moment. Until I started my graduate school education, I shot solely on film. As a graduate student, my pace and interest for time-based media began to change, which is when I sold all of my film gear and bought a medium format digital camera. This felt great at first but quickly started to lose its luster. The large sensor and quick pace made creating videos or traditionally beautiful images rather easy and perhaps too immediate. It bothered me because it felt like I was using the camera to take rather than make.

After graduate school I started teaching full time. My course load included digital and film photography. Teaching B&W film photography made me jealous of my students working with film and made me realize I could synthesize my interest in still image(s), collage and a studio-based practice more organically by eliminating color from my practice, using film and expanding the size of the negative. In the present, I am concerned with how photography relates to production and reproduction as a synonym of propaganda, which is in part a reason why film is an important medium. It allows for endless reproductions to be created, altered and recreated to suit the needs of the user(s).

JF: My journey into photography is quite similar to yours, coming from a skateboarding background when I was a teenager. There is a particular way of seeing the world when you're a skateboarder that I feel is pretty similar to the way a photographer views the world. A staircase isn't just a staircase.

SB: Definitely. They go hand in hand when considering how perspective, symbolism, material and utility can combine. You search for things that others look over and find value within them, sometimes to an obsessive degree. I realized that the ways that skateboarders see the world, in regards to moving through it, is similar to creating art, in that it’s a continual process of redefining what already exists.

When I went to Columbia College as a BA student, I still cared deeply about skateboarding but also began to use the camera to translate the world in a different, more critical way. I can credit my mentor in undergrad, Paul D'Amato who surfs in the cold waters of Lake Michigan, as the reason we're talking. It was him that made me consider how images could be connected in the book form, which I apply to collages, as well as books in the present. That experience also drove me to pursue a masters degree and become an educator.

JF: You were awarded the Visionary Project Award for your series, Angle of Draw. Can you speak to the themes you're working with for this project and how this project has evolved since you received the film grant?

SB: My interests lie in how propaganda supports power systems. I grew up in Detroit surrounded by a deteriorating auto industry and currently live in Wyoming surrounded by the decline of coal and gas. How visual images inform the national imagination surrounding issues of environmentalism, power and industrial decline are all important to me. Though if I were to distill that series and my current practice, I'm focused on how corporate white male systems have misused the medium of photography, misused the world itself and the natural environment to sustain power but also how the medium has been complacent in its misuse.

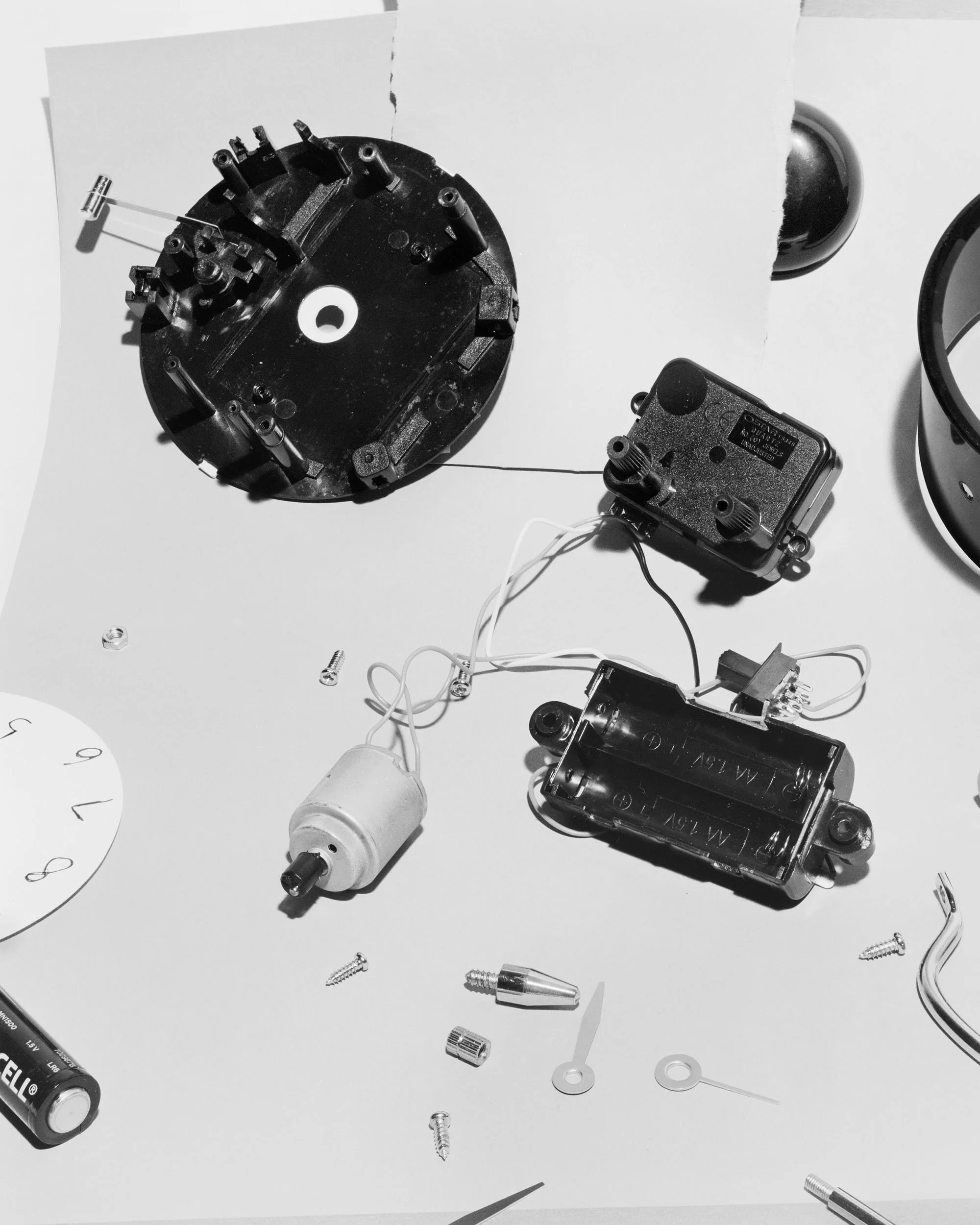

JF: Your practice weaves your own photography with the archive, with ephemera and simple objects in the image. All these elements blend seamlessly to where you can't necessarily tell where things are being sourced from. The end result combines fairly straightforward imagery with deeply complex and at times illusory imagery. It is almost never just a photograph. I'd love to hear some insight on your process and the strategies you use to make work.

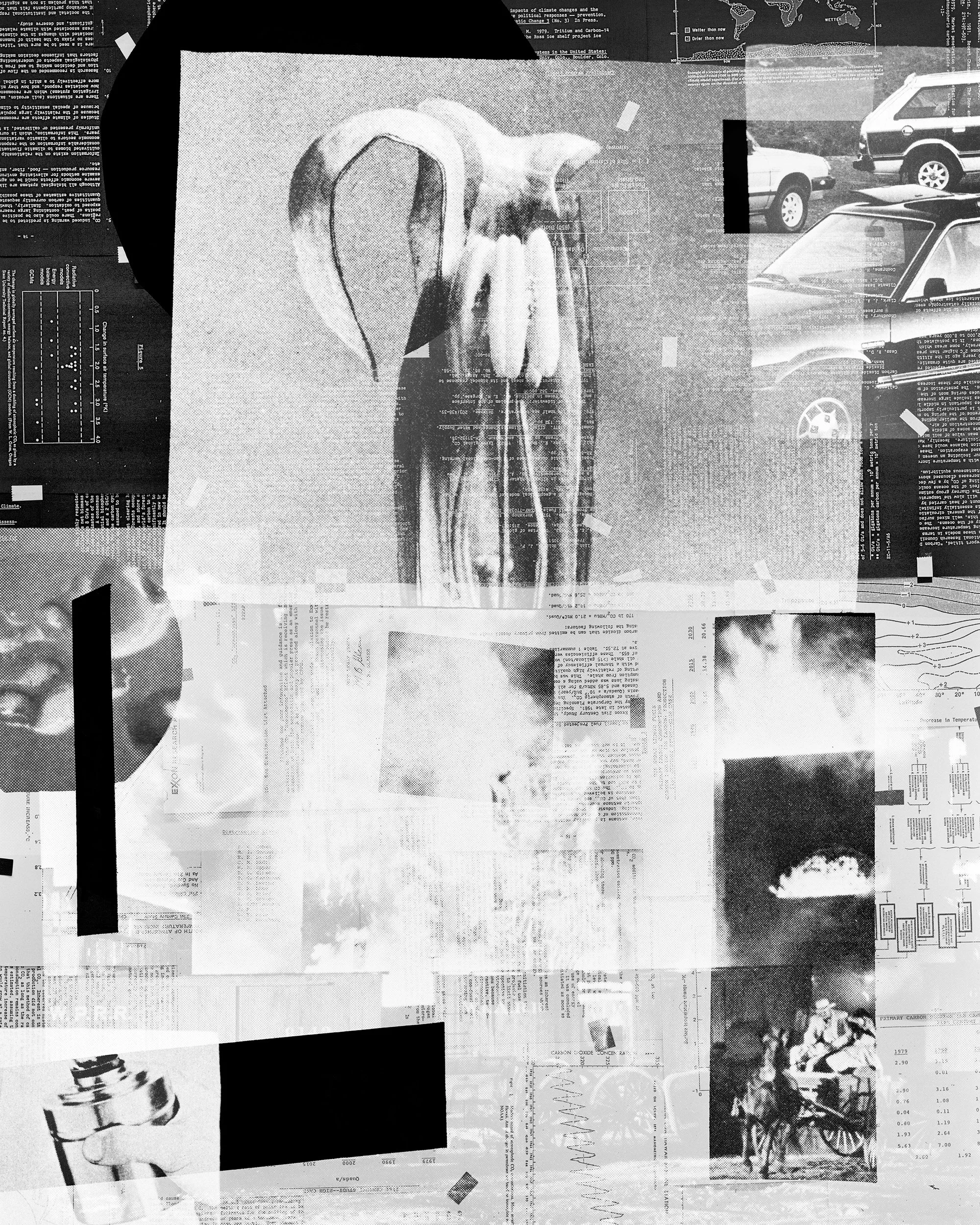

SB: Making work for Angle of Draw allowed me to explore how process, image and material come together in ways that I wouldn’t have without shooting on film and being an educator with access to studio and darkroom materials. A big bulk of production happened at the start of COVID. We only had one semester that was online, but there was that one semester and then the summer where I had the whole building to myself. The building was also being torn down the following year, which meant I could do things that I cannot now, such as paint the large installations up for weeks and paint the ground and walls.

Working in the studio was really responsive at this time, as I was building the foundation for my current practice. I would research and sketch, then go into the studio and just try things out until it felt like the right direction, then go for it. Three days a week, I would make a collage, usually consisting of four or five masks/exposures and then make a still life, develop and scan the film - all in one day. Since masking happens in the pitch black, I'd shoot four sheets of film for collages, and two of a still life. I can't see, and they sometimes fall off or are placed in the wrong area. Quite often there is only one “good” collaged negative. Sometimes it would work out great, sometimes not at all.

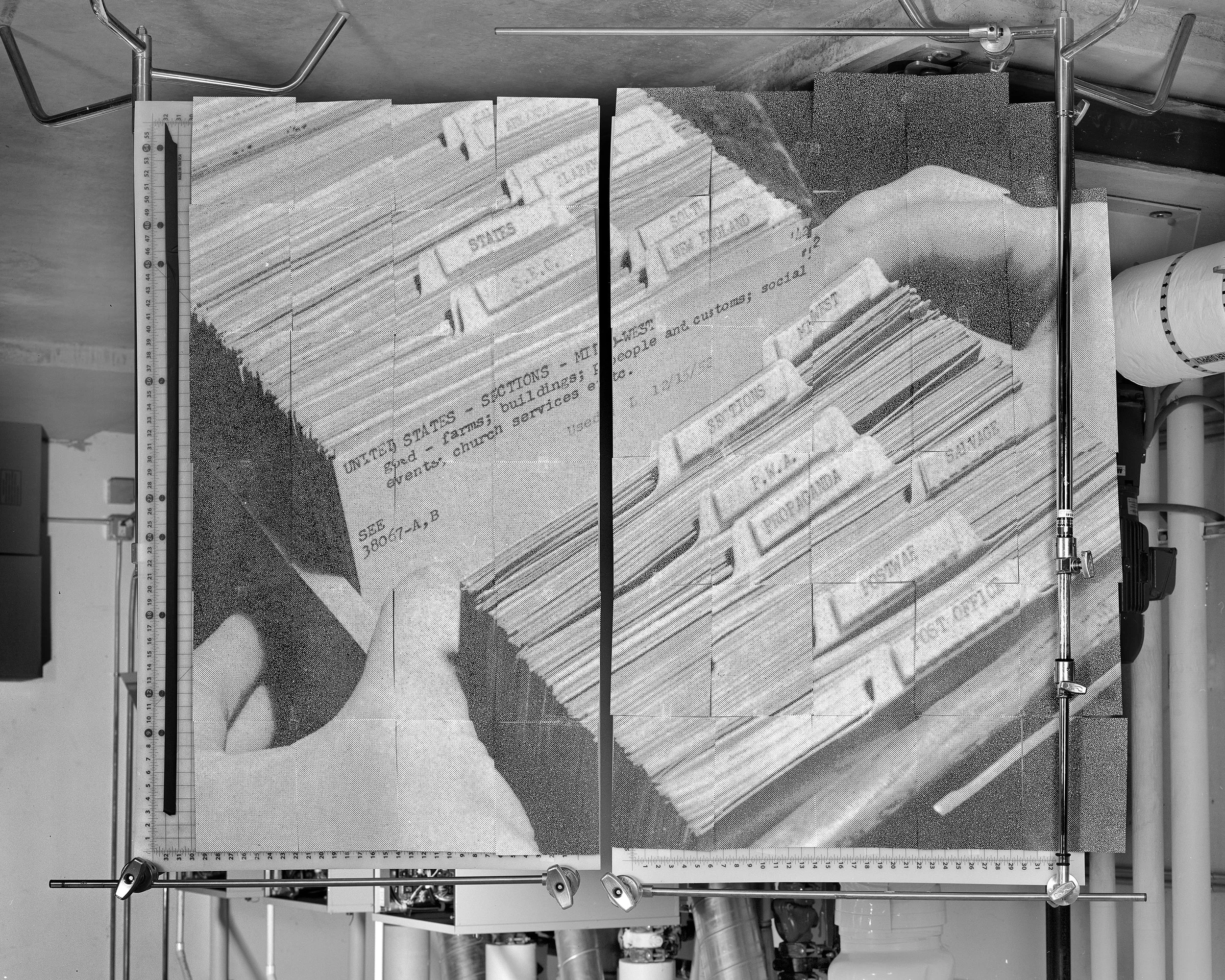

Regarding the archive, I'm interested in vernacular photography, as it is so direct and artless but also refers to the history of images used for commercial purposes. The archives that I have are broad in representation but all produced when Exxon was conducting research for their landmark 1982 internal report, which is important to this work and my practice. Archival images come from spaces which represent my interest in the constructed image, systems of power and nature. Many come from photographic user manuals.

For the Angle of Draw series, I have a couple of strategies which involve physically printing out pictures and collaging them into studio scenes, often as false backdrops, intervening and then taking a picture of the intervention, as well as creating masked multi exposure collages directly onto the film. Sometimes I will employ both strategies to kind of bridge the two so one strategy doesn’t stand out from the other and they mesh. There has to be some visual tie between the two, which is often the lighting and use of materials/forms.

JF: I want to know more about what you mean by collaging directly onto the 4x5 sheet.

SB: I'll make a design in Photoshop with pictures that I take of my phone, either in the studio or landscape and juxtapose them with images from the archive. I'll print that design out, cut out the shapes of images and masks, then trace them onto paper and foam. Foam gets placed onto the film holder in the dark as a reference to where paper masks will be applied, then paper masks are taped onto the negative through the holes. Foam masks are then taped into the camera behind the ground glass. A section of the collage gets exposed, a mask gets removed, a mask gets added, then repeated over and over again.

I plan when masks will be applied and removed to make them achieve a sense of depth, though the magic of masks not being applied precisely allows for double exposing and overlapping to happen. Due to the sensitivity of film and not being able to see where they are being applied to the film, misregistration is inevitable. The slight errors add to the layered feeling and builds from the history of photography and collage. As a result of overlapping and mis-masking, they end up being fractured and imperfect, photographic, but also not. They walk a weird line that I am trying to explore with additional layers and at larger scales.

This collaging process came by as a result of happenstance observation. When setting up a still life, I placed a large piece of black paper down in the middle of the frame, creating a defined rectangle on the ground glass. Seeing the blank black rectangle made me consider if, or how, I could place another image in the black paper through double exposing over that area while blocking out the exterior to integrate two images onto one sheet of film. It kind of waterfalled from there and is now a large part of how I use the medium. Sometimes I will make up to 30 exposures on one sheet of film to create a final piece.

JF: I was fortunate to be able to see your 2023 exhibition of Angle of draw at Candela Gallery in Richmond, Virginia. Most potent to me about this show is that you're able to further expand upon these notions of bureaucracy, secrecy, cover-ups, industrial disaster and troubled histories with the installation techniques you use. Can you share a bit about the importance of installation for you and your general approach in this regard?

SB: I am getting increasingly fascinated with installation as I get more involved with collage and the use of archives, which I think is a reflection of the materiality of the archive and process of

collaging. It is also a way for me to show a bit of the process and the research that went into the work without being direct about it.

For that show, there are a few ways that I approach working with the space, in an attempt to echo content in the images. The first are probably most demanding is a section of a wall that is painted black and has a series of letter sized prints of documents and while male hands in suits along with two collages that reflect content in the letter size print documents. That wall is kind of key to the project, in that it showcases Exxon’s 1982 internal report and provides context to understanding how capitalism, whiteness, androcentrism, industry and natural environment inform the work. My intention is not to have people read the document page, rather feel the weight of them when juxtaposed with the hands and collaged works.

The other strategy reflects my interests in providing context to the content without providing explicit descriptions of them, which is to collage framed works on top of large vinyl collages that were produced in the studio and rephotographed. Unlike the black wall where there are white borders and abundance of contrast to allow the content to advance from the wall, this section does the opposite. The framed works begin to bleed into the wall, which is meant to confuse and conceal.

JF: Why do you think repetition is important to your practice?

SB: It's a reflection of propaganda. Distraction and repetition go hand in hand. We see that all over the place and in varying forms today. We might not believe the lie we are told the first time, but if the same message is said 10, 15, 20, or 100 times, it becomes real and sometimes even “fact”.

Our brains look for patterns to find meaning. Once we are told the same thing again and again, the pattern is embedded in our bodies and begins to drive thought. This is the same strategy the oil and gas industry employed for years, to keep stating their products and business practices are equitable and healthy until society submits.

JF: What does civic identity mean to you? Why is it important? How do you believe it's shifting in our current moment?

SB: I think it depends on, at least in the present, who you are and your background. It's a social responsibility to support the human condition. It is important because it can get us to see other’s perspectives and to create empathy and understanding. Regarding a shifting of the term in the present, I think the polarization of the present makes it hard to do because it is so easy to deprecate something or someone based on one’s own beliefs and find a community who supports one’s ideology, often in social media landscapes where algorithms dominate.

JF: With the rise of AI and echo chambers and things of this nature, how do you feel that propaganda is evolving? I feel that people today are often more easily caught up in propaganda

and lies. Where do you feel that media literacy is in that regard? And how do we improve upon that?

SB: Propaganda is certainly evolving with technology, as it has for centuries. Think about how the printing press allowed innumerable reproductions to be made, creating the mold for mass media that has been built on for hundreds of years. The present is a bit different though. We are in a moment when technology is learning from us and growing, not vice versa. It is scary to think that someone could use AI to embed the intensity of Barbara Kruger’s practice, though skew it for a MAGA base, along with how that tweak could inform the understanding of her decades long practice as an artist/activist who is not interested in supporting those ideals.

In regards to media literacy, we know it's all targeted. If it sounds too good or reflective of your interests and it keeps popping up, maybe question that. Though, the world is stressful and the media can act as an escape, validation of your own ideas, your identity and own self. Sometimes we need that but also need to have the capacity to question the validity of what is being presented to us. But in regards to AI, I think it's both exciting and terrifying. Like any other new tool, it can be used to create and imagine new worlds free of the burdens of the present, or like we see with the current administration’s response to the No Kings protest, it can be used to belittle entire groups of people and demonize them. I am worried about how individuals misuse the tool but also the collective environmental toll of powering the technology necessary for its construction.

When we see how new tools are used and misused, it shows a lot about human nature, which goes back to my interest in photography being used as a propaganda tool to tell millions of people that natural gas is natural. It's all good. Use it relentlessly and don’t think about the ramifications. I don't know if things will ever change because many societies, particularly Western or American society, is so focused on money and prestige rather than equality. There will always be assholes and in a way, I think that is good because it shows us the edge of humanity – where to never go again. That being said, it’s a painful process of understanding that can create generational trauma for comminutes, so if we can acknowledge and avoid these mistakes, perhaps social growth can match that of technology.

JF: What, if anything, gives you hope right now?

SB: I would say the mayoral New York election gave me a little hope. I'm not sure that's going to last, or translate to other wins for American democracy, though it’s a great start.

JF: What's next for you?

SB: I have a book coming out. It will be great to see the past five years of work come together in a cohesive document. I hope the book can honor the research that went into each series and image.

I am also working on a few smaller series that may end up informing a more expanded project like Angle of Draw. One project focuses on climate change through the lens of nature, production, reproduction and image alterations. This project will likely be abbreviated, though I

shot over one hundred and twenty 4x5 negatives of wildflowers with support of the Film Photo Award, and am also considering how they could be used outside of the large collage I mocked. Those pieces will be collaged in the darkroom, rather than in-camera and at a large scale 40x60 inches, or bigger, so I am going to wait a bit until I feel those designs and ideas are resolved before moving forward.

I'm also working on a new series that is not focused on oil and gas, but an industry analog. After reading an article written by Sharon Lerner focused on the chemical company 3M and its misuse of forever chemicals, I became progressively interested in how much their story mocks those of other industries known for malpractices such as energy and tobacco industries. Their story is almost identical to that of Exxon, so for me it's likely the start of tracing a larger survey of corporate misconduct in America through multiple chapters.

I began working on the series using a 4x5 camera but if I get additional grant money, I'm going to buy a 20x24 camera and define my collage work that way, though I am weary of replacing film with paper. I find it more difficult than using film because the multi-grade paper has a natural contrast that must be changed with filters, as there is no chance to change contrast once all exposure is made. If I end up working with a 20x24 camera, I think it will allow me to consider collage in an expanded version and rekindle my love for the straight, or single image by separating the two devices as collage camera and single imaging camera.

JF: I’m excited to see what you make.