Simon Murphy

Photographer Simon Murphy won the Film Photo Award in 2022. Jack Fox and Simon catch up on his work.

© Simon Murphy

Jack Fox: Why is photography your medium of choice and how does film supplement your practice?

Simon Murphy: I found photography working as a postman (mail man). Sometimes I used to deliver postcards with pictures of musicians on. One day, while out on my “walk/route” it dawned on me that in those pictures of the Beatles, Jimi Hendrix, the Doors etc… there was someone else, invisible, unseen in the photograph… the photographer… experiencing all of those incredible moments with incredible people. “What a life” I thought . I left my job and went to college to study photography. I started in 1999. Film photography was still the norm, it’s the medium I learned on. I was inspired by Bailey and Avedon. Those classic black and white iconic images. That’s what I wanted to do. Nowadays, I jump between film and digital, the right format for the right project. For me though… for some reason… I value the images shot on film more.

JF:It seems you’ve gotten to live the life you imagined on those postcards - having photographed musicians like Liam Gallagher and Johnny Marr.

Govanhill is a primarily street photography project shot in the Govanhill neighborhood of Glasgow, Scotland. Having said that you once worked as a postman, I can’t help but think of the relationship of a photographer returning to the same area over and over to photograph being not dissimilar to that of a postman on his route. Did that job inform the work you do today in any way?

Liam's tambourine

SM: Not Liam Gallagher, unfortunately… just his tambourine. Photographed his brother Noel though and yes… Johnny Marr too, he was terrific. That portrait of Johnny Marr is part of an ongoing project on a legendary music venue called the Barrowlands in Glasgow. It’s a quiet celebration of the place and those that perform there… photographed before the mayhem is unleashed.

On the postman job: Yes, there are definite links. When working in the post I would get up at 4:30am and go to the sorting office. The sorting office was full of men taking the mickey out of each other, laughter and occasionally friction. But there was “the walk”. The walk was repetitive and quiet. After a while, step after step after step, I would fall into a meditative state where ideas would flow. I take the same approach when photographing in Govanhill or any project really. I walk and walk. I get into a meditative state where I notice things and people more than I would by just sitting or standing around. There’s something about the repetition that really helps my flow. The other link is, the post was a job. I had to keep going until the job was done. Even though Govanhill is a personal project where I answer to no one, it’s a job that I have set myself that I will see out. I have a fairly strong work ethic being from a working class background.

JF: Well the man and his tambourine are practically synonymous so that is still pretty special. How did you come to photograph the Barrowlands? Did it hold any significance for you in finding the music you love today? I'm similarly interested in how you came to photograph the neighborhood of Govanhill in particular. The subjects often look distinctly comfortable in their environment in a way that gives off the feeling of a small insular community. I'm thinking of Roll 68 (Portrait 2): Cameron. I can see the Avedon in your work, but the subjects often remind me more of a Lynne Ramsay film.

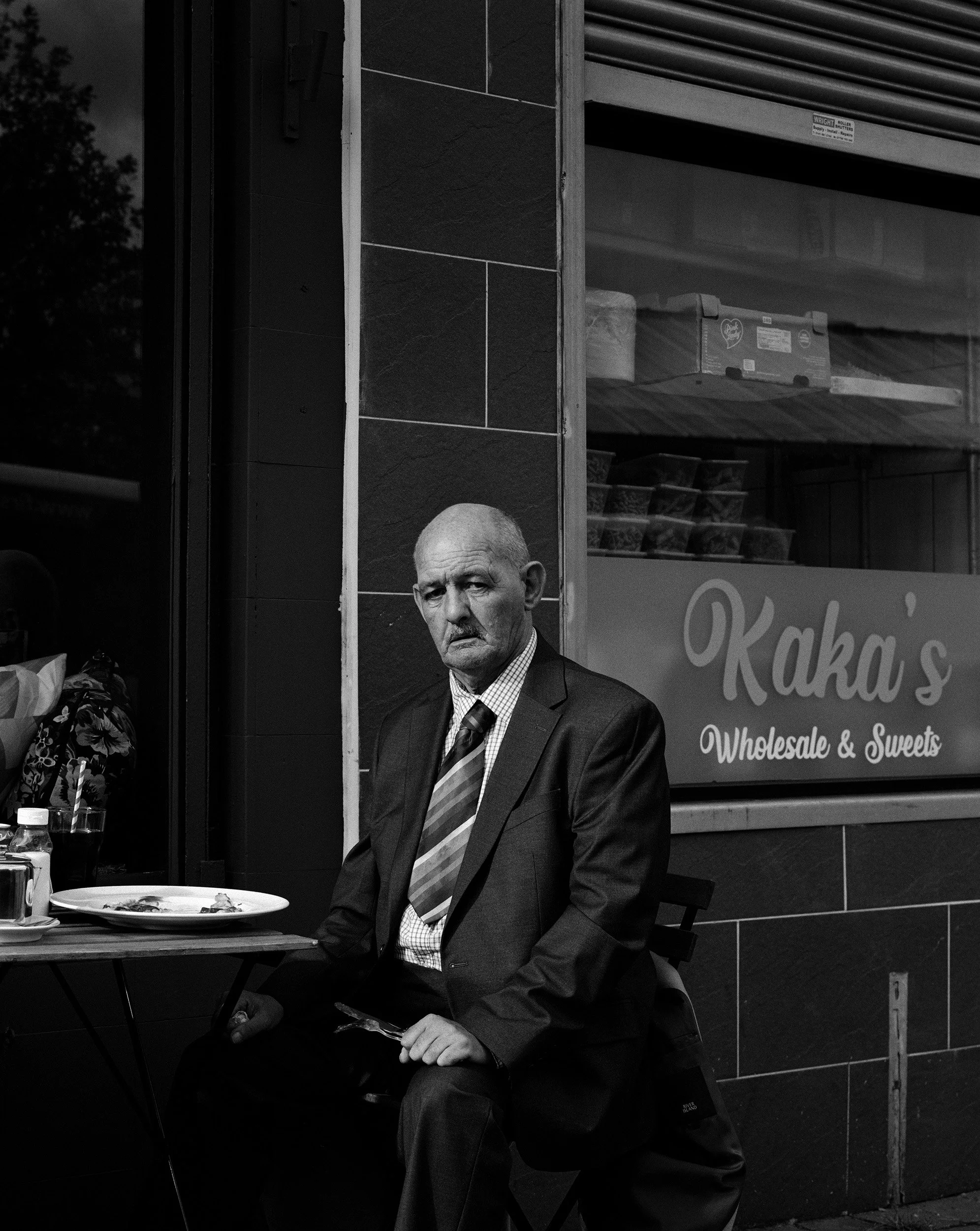

Brian

SM: I guess all of my projects are personally nostalgic. I think projects need to be more than a fleeting idea. To sustain the work needed, the idea should be deeply embedded in your whole being. I take time to really think about what matters to me and what has shaped me over the years. The Barrowlands was a place where I experienced live music when I could first go to concerts with friends, we used to sneak in. The excitement of discovering a new band, trying not to get caught and the ambiance of the place itself still travels through me like the sustained ringing left in my ears as I lay in the quiet of my room after that first gig, eyes wide, unable to sleep and thinking “that was the greatest night of my life”. I feel the same energy when I’m in the building today. Reflecting on it now, it occurred to me that there is something else that I feel, also quite addictive, that runs through my entire photographic approach, and connected to the feeling I would get when my friends and I used to sneak in. It’s the “not knowing”! We faced our fears trying to sneak past a Glasgow doorman… terrified…but if we pushed ourselves beyond our comfort zone, potentially, we could have the most incredible experience. I think that I’m chasing experiences more than the final picture. The picture is just proof it happened.

The Govanhill project is also one that is deeply embedded within me. I used to visit every second weekend as a child visiting my Grandmother who lived there. Then from my early 20’s I moved to Govanhill and lived there for around 16 years. My children were born there. Photography changed my life especially due to how the camera became a passport and physically broke down borders for me as I was assigned jobs in far flung countries. Those experiences in places like Rwanda, the Congo, Bangladesh and Colombia stayed with me and shaped my worldview and my gratitude. The experiences also opened my eyes as to what I had on my own doorstep. What I loved about travel was meeting people from all sorts of backgrounds and cultures. Govanhill in Glasgow is a place where traditionally immigrants arrived in Scotland. The place, only 1 mile squared, is home to 88 different languages. I realized that I didn’t have to travel to have those experiences, I just had to reach out within my own community. I think the people in the photographs look comfortable because they are comfortable. Comfortable and familiar with the place they have been photographed in, comfortable with me (even though I may have just met them) and comfortable with the feeling that I stand beside them, celebrating the place that (even though it’s rough around the edges) has played its part in forming who we are.

JF: That was lovely to hear. Glasgow has been responsible for some of the most incredible music (The Wake, The Pastels, Cocteau Twins!!!). I’m sure you were present for some incredible shows.

To me, the medium of photography has always been inseparable from nostalgia in some way, shape, or form. Like you said, it also gives the operator license to find out about the people they come across and are curious about. That is something that has always driven me as a photographer, and I’ve often been pleasantly surprised at how generous people are with their time and stories. I wonder if there was a conscious moment that you decided the Govanhill work would be a larger body of work, or if it was a gradual realization overtime through wondering about the area that is so rooted in who you are as a person? Perhaps there are specific subjects that made it click for you that this was an important project to create.

It can often be important as an artist to give yourself limitations. With the Govanhill work, you not only stayed within the confines of 1 square mile but you made the decision to limit yourself to 100 rolls of medium format film (the prize this grant awards). How do the confines you set for yourself shape the work?

Francis

SM: I think the seeds of an idea are there already, planted deep in the subconscious, but like a tree it needs time to grow. There is no need to rush the process, before you know it, the idea is towering above you. The seeds of ideas are planted by wandering and noticing. It’s so strange, I had an idea for a project that I’m currently working on about a year ago. I came across some lost negatives the other day and I was stunned to find that there is a whole series of the very thing that I’m photographing now for my new project that I made on a random wander about 13 years ago. That idea has been growing without me knowing it for more than a decade.

The Govanhill project was a bit like that in the sense that, whilst not always making photographs, for years I had absorbed the place, the streets and the people. The love of the place, even with its rough edges, had grown in me without me really realizing it.

Twins

I came across a quote that resonated and is linked to all of my projects. “The enemy of art is the absence of limitations” - Orson Welles. We all have limitations, sometimes physical, sometimes circumstantial, sometimes financial. I had plenty of limitations growing up but when you realize that limitations are actually a blessing and that they can actually make you more creative, that’s a lightbulb moment. Creativity is about finding solutions in the face of barriers. Now, I don’t just recognise that I have limitations, I actively base my projects around them and use them to push myself to be more creative and productive. For example: The award of 100 rolls of film. That’s a limitation albeit a very generous one. I knew I needed to make each roll count because I was quite literally counting them. It took a while to begin as I knew that a strong start would set the standard for the entire project. I carried a box of the film with me waiting for the moment that felt right. When I saw James and Brian sitting on a step together, I knew I had my start. After that first roll, I had to keep going. It took me about 6 months to complete and I don’t think I would have been so productive if I never had the limitation of the number of rolls and frames.

JF: Govanhill was published in book form by Gomma and coincided with a solo exhibition at Street Level Photoworks in Glasgow. Sequencing a book and sequencing an exhibition are two entirely different things. The feeling of a body of work can change entirely from book to show. How did you approach both of these aspects of the work?

SM: When it came to sequencing the exhibition, I started with a question: What does it mean to be part of this community, Govanhill? I started with the outsider's view. Growing up, it was only negative stories that I would hear about the place, whether that came from the media or people who didn’t live in the area. The first image wasn’t a portrait, it was a very rundown stairwell in a tenement building. In many ways the image lived up to the reputation… rough and intimidating. At the end of the corridor was a closed door with light flooding underneath. The idea was… “Ok…yes, this place can be rough around the edges, but what’s beyond that door? Look a little further!”. The next image was a tattooed man staring directly into the camera. Again, the image was confrontational and possibly intimidating but then you notice the word “family” above his eye and you realize what is important to this individual, the very same things that are important to the viewer. After that I broke the exhibition up into sections dealing with the foundations of the community… family, roots, culture, shops and pubs etc. the exhibition ends with the future of any community, the youth.

There was a separate room for the “100 rolls” project. I had so many images and wanted to show at least one image from each roll. There were so many that some had to be printed small. Honestly, for this part of the show I just printed the best shots really big and worked the rest around that. I also displayed each of the contact sheets from the 100 rolls. In a way, this room was for the people interested in the process.

The book was an entirely different experience. The publisher sequenced the images themselves. I just wanted a book published to coincide with the exhibition. Initially, it was a dream come true so I went along with it even though there were some major red flags that turned out to be very real.

JF: Hearing that, it occurs to me that you are very good at making decisions that make a body of work more cohesive. I.E. 100 rolls, neighborhood parameters, image categories. Breaking the exhibition up into these broad categories allows you to sequence the photographs in a way that allows certain images to work together when you may not normally think they would. I'm quite keen on the idea of putting your contact sheets on display in completion. Many photographers, myself included, wouldn’t be comfortable with displaying all the mistakes you made along the way to the final images - an admirable decision and I’m sure educational for many viewers.

For the book, may I ask what those red flags were? I think it would be helpful for readers as many may not have had a behind the scenes look at a publishing house. Each one functions incredibly differently with different capabilities. Are you content with the finished product? I’ve not had the chance to see a physical copy but from what I’ve seen online the design was done beautifully.

Photoautomat2

Photoautomat1

SM: On publishing: I’m not negative about the experience, I wanted a book to coincide with the exhibition and that (almost) happened. There were publishers with a stronger track record that were interested in the project but the turnaround time would have been difficult. The publisher I went with said they could do it and offered a fair contract too. Because the project was based in a community that faces difficult economic conditions, I was keen that, after the initial publication had sold out, that we would make a more affordable and accessible version for the community. There was a second edition but my ideals didn’t align with theirs. I’ve only had dealings with one publisher as this was my first book and many of the broken promises only came to light after they had published a second edition. Everyone told me that you don’t make money from photo books but the company didn’t even honor the royalties that were written in the contract. The early warning signs that I brushed off, because I was so excited about the project, were definitely based around communication. I did find it a little odd that the company, even in the initial discussions, wouldn’t agree to a face to face meeting or even a zoom call. Unsurprisingly, the pattern of poor communication continued with those that purchased the book and who did so thinking that they were supporting me. Some hard lessons learned but lessons are lessons and are valuable whether positive or negative.

On the contact sheets: I teach photography and too many students feel the internal pressure that every time they click the shutter, they expect a masterpiece. Sometimes, the photographer, through fear of admitting that failing is part of the process, will use confusing and cliched jargon in a statement to try and pull some kind of Jedi mind trick on the viewer. Some of what I do doesn’t quite meet the mark, I’m comfortable with that. When I make mistakes, I learn and then I can pass on my experiences to others. My wider mission is to celebrate the medium that changed my life, this amazing thing called photography that can bring experiences that would be hard to even dream of. I think an honest approach makes it more accessible. Of course, there is risk for the photographer who exposes the mistakes as there are those that will use that approach to tear apart and undermine the artist but those people tend to live in online forums, I deal with real people and real faces. What’s most important isn't the mistake but what you do after that. The ability to persist and see the task out despite setbacks is inspirational. I love contact sheets for that reason, they reveal the process in getting to the final selection. The hesitance, the fear, the awkwardness and the beautiful triumphs.

JF: I completely agree! It makes me think of my university education being shown the contact sheets containing Dorothea Lange’s Migrant mother and the frames leading up to the final, iconic image. You see a sort of time line of Lange approaching from afar and slowly getting closer, having the subjects try slightly different poses until landing on a photograph etched into the canon photography. It’s so informative to see the process behind images and realize how much impact a minor shift in a pose or angle can have. A photographer, or artist for that matter, doesn’t exist that hasn’t made thousands of mistakes in the process of arriving at a triumph. Can you tell me a bit more about your approach to teaching and if it has shaped/ changed your practice in any way?

Lula

SM: It might sound surprising but not every student who enrolls in a photography course has aspirations about turning it into a career. Funnily enough, some roll their eyes when you ask them to take photographs! In Scotland, everyone gets four years free education at a higher level. This is a great thing that should never be changed as it gives people an incredible opportunity to change their lives. At the same time, anything that is free, can easily be taken for granted. When I first started teaching, my intention was to try and make everyone professional but now it’s more about helping students to understand how powerful the visual language is and how many of the softer skills that are developed in photography (communication, problem solving, resilience building) can assist in other areas of life. Because I teach, I feel that, much more than before, I’m trying to draw lessons out of my own process and projects to help inspire others. Often, I undertake assignments at the same time as the students just to help me understand the process from their perspective as things change. Teaching for me is about understanding the challenges but encouraging the students that all the best things in life lie just beyond their comfort zone. At the root of it, all of my projects are actually a celebration of photography, the medium that transformed my life and gave me so many rich experiences. My teaching is an effort to try and convince others that a camera could do the same for them.

JF: As a person whose education was quite expensive, I’m envious of that. Like most everyone I know I am hopeful that we can one day have free or at least affordable college here in America. Though I can see how not having to pay for a photography class may make some not take it as seriously. I love that you make work for your assignments while your students do - it seems like that would show someone who is just starting to learn the medium what is possible when given a prompt. How vastly different work can come out of two people making images in the same place.

What can we expect to see from you in 2025?

SM: The Govanhill project took about 6 years and the “100 rolls” element added around a year to the project. Apart from a few commissions here and there, it was my sole focus . Having the exhibition felt like a natural conclusion to this chapter of the project and gave me a chance to develop some other ideas. Currently, I have three different projects on the go. The Barrowlands music venue project which I think will need at least three years to collect a solid body of work. Another project is a collaboration with my old high school, King’s Park secondary and I am also currently working on a project based in Berlin which is the one most likely to be unveiled first. I’m in talks about an exhibition that I would love to run in Berlin and Scotland at the same time. I’m planning a new book for the project and investigating the best way to go about publishing it.

JF: Before we wrap up, could you briefly describe the two projects we haven’t discussed yet? If it wouldn’t be spoiling anything that you want to keep under wraps while you make the work.

Bowl cut Bob

SM: Kings park: a portrait of diversity. This is a project that I’m shooting in the same style as Govanhill. Medium format film portraits of people (mainly pupils) that attend the school. I’m trying to encourage the pupils to write poetry, essays and to conduct interviews with fellow pupils on the theme of “Belonging”. Like Govanhill, it’s a celebration of Diversity.

The other project is based around the photoautomat machines of Berlin. Again, I like the idea of restrictions. Govanhill was photographed within a mile squared… Photoautomat is photographed within and around boxes around two meters squared. I wanted to do something completely different from Govanhill. Digital. Colour. I also decided that it would be a project of landscapes and details rather than people but people are what I’m drawn to so after around 5 visits trying to avoid the human element… they have found a way in.

JF: I wasn’t aware that Berlin had so many of these around the city! Each project you choose seems like an entirely different environment and challenge. Truly looking forward to seeing how all of these pan out. I appreciate your time and generosity in your answers. Thanks Simon!

SM: Really enjoyed the interview… especially when we touched on the Barrowlands work as it helped me consider some of my reasons as to why I embarked on it and revealed things to me I hadn’t fully considered. Very best wishes Jack.