Emma Ressel

© Emma Ressel

JF: What initially interested you in photography, and what keeps you working in this medium? Why film?

ER: I had some cool early experiences photographing with my dad. I grew up in Maine, and my dad was a biology teacher for 30 years at a small college there. He studies reptiles and amphibians and when he had sabbatical we would go to Tucson, Arizona because there are a lot more reptiles in the desert than there are in Maine.

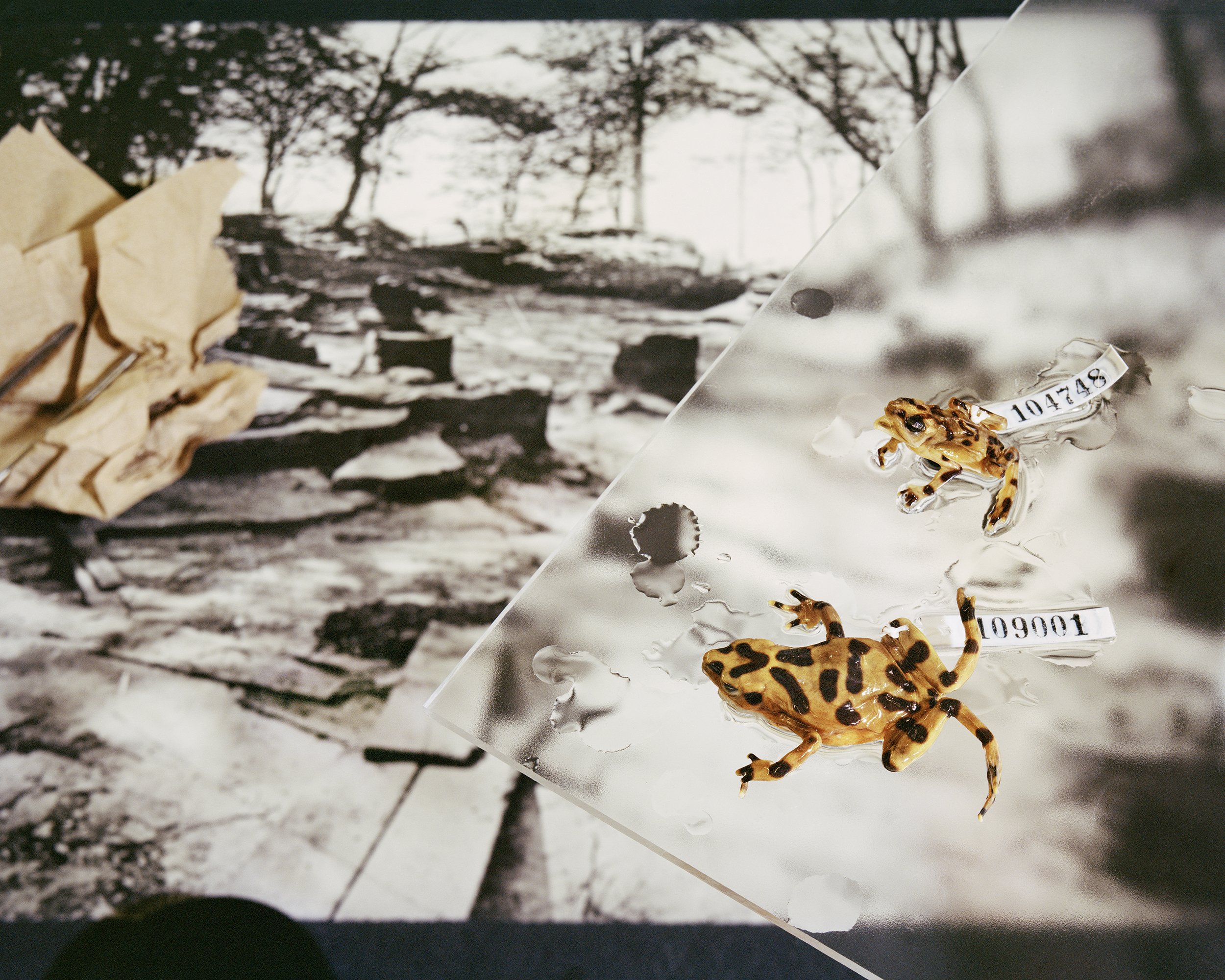

drying chamber, 2023

cretaceous understory, 2025

This was in the early 2000s and he was making 35mm slides of the species that he taught in his classes, which he showed on a Kodak carousel projector. I would help him set up these shots; we would catch lizards and put them in the refrigerator to cool their body temperature down so that they moved very slowly. Then, I would help him position the lizard on a rock and compose a picture that was naturalistic but had these staging interventions. These were really fun, early introductions to photography, and eventually, I wanted to start shooting with a digital camera. I got a little Canon Powershot for Christmas one year. Then in 2008, all of a sudden, I wanted to go back to film and I started borrowing my dad's cameras again. I took a workshop at Maine Media Workshops in high school where I got into the B&W darkroom, which was pure magic for me. I really love repetitive methodical tasks and the darkroom satisfies that part of me. I studied photography in undergrad where I got access to the color darkroom, which I would still be using if I could find access. Learning how to print color film was an important education for me and influences how I edit my pictures in Photoshop. I've been making still life photographs since undergrad, and I think of those early experiences posing the lizards for my dad as a still life compositions as well. I started making still lifes with a large format 4x5 camera and I loved using the swings and tilts to subtly influence the focus plane. This is what I am still doing.

JF: When I was looking at your work, it occurred to me that so much great work is coming out of Maine these past few years. Do you have any perspective on why it's such a hotbed right now of great art?

ER: I am feeling FOMO that I am not there at the moment and part of what is happening in Maine! When I was graduating from undergrad, it was still a time in which I was hearing that I had to live in New York or LA to work as a photographer, so I didn’t think that Maine was a place I could have a career. The work happening in Maine right now is so incredible and important for shaping a photographic identity of the region that is more multifaceted than we’ve seen in the past. There is a darker side to Maine than the beautiful scenery, sailboats, and quaint New England charm, and I’m so happy to finally see that complexity reflected in this new wave of art. I’m following it closely and super proud. The longer I live away the more I feel tied to Maine, and the work I am making now is directly related to my perspective growing up there. I hope to support my friends and colleagues working there and tap in as much as I can.

JF: Is the grad school you chose what drove you primarily to move to New Mexico?

new mexico bone bed, 2025

ER: Yes, it is. When I was applying to grad schools, I was living in Philly and mostly working in New York, and spending a lot of time on I-95, going back and forth between the two. I was kind of floating between the two cities, and while I wasn’t expecting to move across the country, going to New Mexico afforded me a break from an unforgiving schedule. University of New Mexico caught my eye because in addition to its strong photography program, the MFA program also hosts an Art & Ecology discipline, which I knew would be an important area of study for the ecological concerns in the work I was interested in making. There also happens to be this incredible natural history museum housed within UNM called the Museum of Southwestern Biology. Not only was UNM a great place to study photography, but I also had the resources to continue down this conceptual path. I’ve fallen in love with Albuquerque over the past three years of living here. I'm sticking around because I love New Mexico and my community here, and I was not expecting to love it this much.

deep time storage, 2025

JF: Much of your work is made using natural history museum archives, objects and specimens, and so forth. Has it been challenging to gain access to these institutions, and what has your experience been like working within them?

ER: It's certainly been a bit of a dance to get into the collections, and the process of gaining access has influenced which museums I’ve worked with and which specimens I’ve photographed. The first museum I went to was the Dorr Museum at College of the Atlantic in Bar Harbor, Maine, where my dad worked. His office was on the second floor of the museum for as long as I can remember, and I was very familiar with the dioramas which hadn’t changed much at all since I was a kid. I was able to not only bring my camera and tripod into that museum, but also photo backdrops that I started placing behind the plexi boxes. Then from there, I tried to follow connections and word of mouth as much as possible. When I got in touch with collection managers I would show them the photographs I was making so they could understand the purpose of my request. The longer I worked on the project and the more I learned about collections, I became more interested in the decay and the breakdown that happens to the specimens and dioramas over time. I like working with smaller museums because there is less red tape, more opportunity to have extended interactions with the folks who work there, and more windows into the cracks in the facade. Working with the Museum of Southwestern Biology, I had to go through the motions of filling out official loan paperwork and write about why my request to photograph specimens was important to my “research”. This was a challenge at the time, but ultimately was a very helpful lesson in framing my work as legitimate artistic research.

JF: Your work is very much a critique of the Natural History Museum. What would you change about the way these institutions function to more adequately address the issues that they're facing?

ghostly middle, 2023

ER: The work is definitely a critique, but it’s also important to me to stress the importance of natural history museums, especially the science that goes on behind the scenes that has nothing to do with the public dioramas. In fact, at all the major natural history museums, the majority of the museum's activities are involving new research, which I am absolutely in favor of. However, I am skeptical that the outcomes of this research are going to change any conservation policy, which is more of a critique of the place where science meets politics, separate from the existence of the natural history museum. I don't think that showing, let's say, an extinct bird in a natural history museum is going to engender such awe and respect in the general public that other species of birds will not not become extinct. I think the issue is too large. I would love to see natural history museums be a little bit more honest with themselves and with the general public about what their purpose is now and going forward. I think they're becoming more like memorials for the animals that have lived around us. We may no longer have any ability to see X animal in the wild, so we need to see it in a museum to learn about it. If anything, I think the museum as a memorial will become an increasingly important place for us to reconcile these disorienting environmental changes and losses.

JF: The pessimistic thought that runs through my head, that as we move towards the future, we seem to be heading in; this is going to increasingly be what our experience with nature is. I'm wondering if you could give a little perspective on the state of nature conservancy, and if there's anything that gives you a hope on that front?

ER: I completely agree with you about that. My research into the history of these museums tells me that this has been one of their main roles since the beginning. For example, I was just at the Academy of Sciences in Philadelphia two weeks ago, and I was looking at a diorama of Bengal tigers. I was probably two feet from the tigers, though of course there was a huge piece of glass in between us. I had this experience of feeling almost a little scared, like, oh my gosh, this is an animal that could kill me easily. The only way I'm able to have this experience is because the tiger is taxidermied so well. The natural history museums provides that experience, but it is always just an approximation of the real thing.

false paradise, 2023

The town where I’m from is the entrance town to Acadia National Park and I grew up thinking the role of the national parks was to preserve untouched nature, but I’ve more recently learned that nature was never untouched, and that idea erases the people that lived there before. The way that we invent nature is full of layers of fictions and narratives. Natural history museums are a good place to look to see how those fictions are built.

I am pretty pessimistic when it comes to thinking about environmental futures. I feel like I’ve been waiting my whole life to see policies change and for more land and species to get protected. Now, the opposite is happening, protections that have been there are getting eliminated. My approach, which I bring into this project, is cultivating attention and awe for what is happening around me. As sad as it may get, it’s also going to get really interesting. What happens when invasive species move into new ecosystems is undoubtedly interesting, as well as the way the ecosystems are changing due to temperature and seasonal shifts. It won’t just fall apart, there will also be collisions and interactions we won’t have anticipated.

Did you hear about this species of oarfish that have been washing up on the Pacific coast beaches? This is a deep sea fish that is super rare to ever be seen by the human eye. In Japanese mythology, they are known as the doomsday fish. Oarfish washing up on the shore from the depths is a harbinger of doom, and in the past few years there have been quite a few sightings. The years I was living in Philadelphia, I saw the spotted lanternflies rapidly invade Pennsylvania. They were everywhere. It was awful, but it was also fascinating, and the lantern flies are absolutely beautiful. I do not want my despair to keep me from looking and paying attention.

JF: Have you made images of the spotted lanternflies?

ER: I haven’t, but I should!

JF: Your work is clearly very planned out, can you shed some light on your process from inception to the moment you click the shutter?

last seen in 2009, 2025

ER: These days, I'm trying to be intentional about which species are in the image, but I like to leave a lot of it up to circumstance as well. When I've been photographing in the collection rooms, I will have an idea about which animals I want to photograph and I will bring some options for photo backdrops, but I'm also hoping that I can incorporate objects and textures from the rooms I’m working in.

In some images I let the backdrop extend past the edges of the frame which pulls the taxidermied animal out of its context in the museum and places it in some fictional habitat. Then there are times where I don't let the backdrop reach all edges of the frame so that the elements of the museum, table, and work surface come into play. It’s important to me to have a lot of control, but not to much.

whooping crane efforts, 2024

I set up the camera on the tripod and built the still life to fill the area of the ground glass. I often use some added light, and sometimes make an instant film test with instax film in a 4x5 back.

JF: I'm curious about the backdrops, which feel very vital to your practice. Are you making those yourself, or are you finding them? What's going on there?

ER: The question of the backdrops was a complicated one to solve when I first started making this project. If I'm going to alter the context of the animal, then what am I going to say? The earliest backdrops I used were paintings made in Maine by the Hudson River School painters. I studied the Hudson River School in my art history classes at Bard College, and I learned that the painters also traveled to Mount Desert Island. When they painted MDI, they really dramatized the landscape and changed elements of the land such as the profile of a cliff, or adding a tree, that kind of thing. I saw that these early 1850s paintings were already doing the same fictionalization and dramatization process that the natural history museums and even the national park project does. Over time I started using my own photos as backdrops. Sometimes they were photos that didn’t quite work as standalone images. Layering them became a way of building up the original image.

JF: Those paintings I believe are considered part of romanticism. The critique of the romantics is often that they were romanticizing something that has an ugly underbelly of some kind, and that feels very apt for the work you’re making.

red efts in the full moon, 2023

ER: There are religious undertones to those paintings, the sublime skies are pointing towards a Christian God, implying this land is for Western settlers. Through the foreground, middle ground, and background, there are implications of westward expansion, colonization, and sometimes vilifying depictions of Native people. This is something I am concerned about in my work. How do I talk about natural history without repeating these compositional tropes and perpetuating old myths? I can't say that I'm fully succeeding at subverting them, but what I do think I have done is distorted and in some cases compressed the image plane. You could maybe say that I’ve eliminated the middle ground; there is only the animal and the backdrop.

JF: At their core, those paintings are really just propaganda images. I had never encountered lantern slides until looking at your work. What are those exactly?

ER: I am relatively new to the world of lantern slides! I came upon them from working in these collection rooms, and I learned that not only do a lot of these museums have preserved animals, but they also have photo archives. Natural history museums might have boxes of slides, maybe a personal collection of a scientist or professor, like my dad has his collection of 35mm slides. Glass lantern slides are simply the precursor to cellulose slides. They were really ubiquitous between the 1860s to whenever the Kodak slide took over. The glass lantern slide is about three by four inches, and it's two pieces of glass with a silver gelatin image printed directly on the glass and taped closed. The images were projected in magic lantern slide projectors and were most typically used for educational purposes, including art history lectures in particular. They were also used for propaganda; traveling lecturers would give magic lantern slide presentations on whichever topic, including religious sermons.

shifting baseline syndrome, 2023

The collection that I worked with was used by an earth and planetary sciences professor at UNM 100 years ago. They contain images of dinosaurs, mammoth teeth at University of Nebraska-Lincoln, and sorts of different science-y images and charts. I couldn’t find any contextual information about this collection other than what was on the slides, so I was thinking about archival decay, not dissimilar to an animal decaying, losing context, and becoming a mysterious image of science from the past.

It’s hard not to think a lot about Evidence by Mike Mandel and Larry Sultan and how that project examines scientific imagery in a poetic, decontextualized way.

JF: You won the Film Photo Award for your project Glass Eyes Stare Back . Can you speak a little bit about this project specifically and how it's evolved since receiving the grant?

sottobosco after otto marseus van shreick, 2024

ER: Everything we've been talking about is what I'm thinking about with Glass Eye Stare Back. The title and a lot of my research comes from a book called The Breathless Zoo by Rachel Poliquin. She argues that natural history museums and animal taxidermy are born from a very human longing to draw nature closer, but in a museum the fulfillment is always just beyond reach. The museum is an expression of our attempt to negotiate our uncomfortable relationship within and outside of nature. Poliquin’s ideas explained for me why I felt drawn, after however many years, to come back and look closely at this one museum that I had been going to my whole life.

I treated the dioramas as a still life composition in my approach to photographing. Because there is a rich history of photographers working with natural history museums, it was important for me to ask questions about the future and the memorialization that I see happening in natural history museums.

My 4x5 camera felt like the best tool for me to use to describe those qualities. I think a lot of photographers wonder about how much longer they can hold onto shooting film before needing to let it go. Shooting film feels like it ties me, my work, and my process to this long lineage of photographers working in a certain way or simply working with a certain color palette, determined for us by Kodak. I love using the color gamut of the film to help shape the colors of the project. I also enjoyed a certain symmetry to using a type of camera that was around when a lot of these specimens were prepared. The Film Photo Award is the reason that as much of this project was made with 4x5 as it is. When I received the award, it was the first time I started making more than one exposure for each of my images. Having the bandwidth to use two or three sheets helped ease a lot of pressure. This is the best prize that exists in photography because it just gives you the tool you need, like giving you the paint. It’s incredible.

JF: What's next for you?

ER: The slides! I found that collection of glass lantern slides toward the end of working on my MFA thesis project, so even though the slides are incorporated into my thesis work, I still feel like I have only scratched the surface of working with them in an informed way.

prep lab, 2023

I’m now doing a year-long postdoc fellowship at University of New Mexico in the Center for Regional Studies, which is an interdisciplinary research center here at the university. I proposed a project to scan slides at many different science and history museums across the state of New Mexico. I'm going to see what I find and work with the slide imagery in new ways. So far, my parameter is that the slides have not yet been digitized by the museums that they're housed in. I’m using a dslr scanning set up and giving the museums the scans to add to their databases. I'm learning a lot about what slides looked like, and that certain slides can turn completely pink over time. It is an exciting next step in making work in a research framework. I’ve also had some exciting opportunities to show Glass Eyes Stare Back, including in a show at the Houston Center for Photography that will be up until January 4th. The work I made with the Film Photo Award is getting out into the world, and that’s really amazing.